We hovered over the top of a dune, sizing it up, then landed gingerly. The gray sand was blown away in rivulets and the sparse, dry grass bent in the prop wash. The helicopter's wheels settled in the sand. We ran down the slope, with the sand filling our shoes, and leaving tracks that filled right in.

We had not been expected. After spotting a flock of sheep in the desert we had landed by the campfire out of plain curiosity. We said: "Salaam" and three men replied: "Salaam". This was probably the first time a helicopter had landed beside their flock, but not one of them approached it. Still, they were as curious as we.

The flock consisted of about four hundred sheep and two goats with brass bells around their necks. The sheep had meekly accepted the leadership of these two bearded sages and now followed the tinkling bells in a solid mass. Two asses started a fracas beside the fire, with the black one managing to get in a few good kicks. The gray ass bolted and shamefacedly joined the sheep. There were also eight camels, three gentle dogs, the three men and one small fire for them all.

It was cold. Oh, how bitterly cold and depressing it is in the desert in winter! The rippled sand stretched on and on. One might imagine that something did grow here early in summer, something green that perhaps even blossomed. But what could a flock find to eat in the cold sand now? The camels were chewing on something, grinding their yellowed old teeth. The goats had climbed to the top of the hill and were inspecting the helicopter. One had placed its forelegs on a wheel. Then, getting a whiff of the gasoline, it snorted and backed away. We all smiled: the pilot and I, the two young shepherds, and even the old shepherd, who hid his smile in this tattered sleeve.

We held our hands over the fire. Saksaul twigs burned hotly beneath the bubbling, sooty, dented pot. The old man fished a flatcake the size of an umbrella from his sack. He divided it equally among us. A chunk of flatcake and a scalding mug of green tea are one of the greatest joys in this bleak season.

We did not speak. The only word of Turkmenian I knew was "salaam". That was about as much as the old shepherd knew of Russian. However, the tea and the flatcake helped us to get acquainted. They understood that I was from Moscow. I, in turn, managed to learn that the old man had been tending sheep in the desert for twenty years and that his son, Hodja Guldiyev, was killed in action during the war near the city of Orsha. The old man brought out another flatcake and poured us more tea. I believe that even very talkative people become reticent in the desert. However, this silence is but the silent conversation of people gathered around a campfire. In these twenty minutes I realized that a chunk of flatcake and a mug of tea in the desert are not at all the same as having tea at home, and a few words spoken with reserve here carry much more weight than the same words spoken elsewhere.

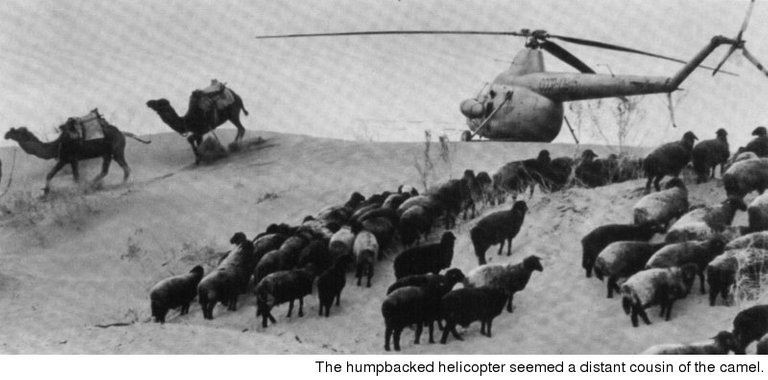

A man leading two camels appeared from behind a hill. The second camel's bridle was tied to the first earners tail. Where had the man come from? And how had he got here? He had obviously been attracted by the helicopter. However, he led the phlegmatic beasts right by it without once glancing at the iron bird. The youngest shepherd laughed at the sight of the procession. Then we all began to laugh, for our humpbacked helicopter in some strange way resembled a camel. The old shepherd appreciated the joke, too. I saw him smile broadly for the first time.