The weather is getting better and I'm seeing more and more insects. The larvae of bees, wasps and ants have grown up, and the adults are using their free time to find sugar. Seeing all these creatures reminds me of a particularly interesting scientific experiment: the pain of insect stings.

Tarantula hawk wasp stinger. (Photo: Rankin1958 via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0)

A sting is not a pleasant experience, regardless of whether it's from a bee, wasp or an ant. The order of these insects - hymenoptera - is a big family, with approximately 156,000 species. Is the normal expression "ouch" applicable to all of these ladies? (The stinger is actually a modified ovipositor - egg-laying tube - and so only the females can sting.)

Justin O. Schmidt, an American entomologist, wanted to find out the answer to this question. In a laboratory it's not difficult to find out how venomous a sting is, but danger and pain are not the same thing. How can one measure pain? There was only one solution: Schmidt allowed himself to be stung by numerous different insects. The Schmidt Pain Index is a wonderful index of his experiences, and consists of a scale of 1 to 4. Insects whose sting doesn't actually inflict any pain are not mentioned in the index.

What is particularly notable is the descriptions, which are often poetic and funny. Schmidt would have been an excellent wine critic. Small bees such as blood bees and sweat bees have a number one:

"Light, ephemeral, almost fruity. A tiny spark has singed a single hair on your arm."

The sweat bee (Photo: Alvesgaspar via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Fire ants get a 1.2:

"Sharp, sudden, slightly unnerving. Like walking on a carpet & getting a static electricity shock."

Fire ant stings (Photo: Daniel Wojcik via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

At 2 is the benchmark that we all probably know, and the benchmark for Schmidt's study: the honey bee.

"Like a matchhead that flips off and burns on your skin"

Apis mellifera, the European honey bee (Photo: Ivar Leidus via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0)

Apis mellifera, the European honey bee (Photo: Ivar Leidus via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0)

I have seen an interview with Schmidt in which he says that honeybees are the most dangerous, simply because there can be so many of them in a hive.

Schmidt rates the majority of stings as a two. Things get hotter at three. In this category are insects such as the red paper wasp and the velvet ant, which is actually a kind of wingless wasp:

"Corrisive, burning and relentless, as though someone has used a power drill to expose an ingrown toenail or poured a cup of hydrochloric acid over an open wound."

The stinger of polistes carolina, a paper wasp (Photo: Alexander Wild via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

The stinger of polistes carolina, a paper wasp (Photo: Alexander Wild via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

Things get particularly interesting at level 4. The Tarantula Hawk wasp is armed with a 7 mm stinger. Schmidt writes about this wasp:

"Blinding, fierce, shockingly electric. A running hair drier has been dropped into your bubble bath."

The Tarantula hawk wasp (Photo via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

And the worst sting? That award goes to the bullet ant, which is so called because the pain has been described as akin to being shot. In some south American cultures to which this ant is native, it is known as the 24 hour ant - because of how long the unbelievable pain lasts. This ant has its very own chapter in Schmidt's book. He writes:

"Pure, intense, brilliant pain. Like fire-walking over flaming charcoal with a 3-inch rusty nail grinding into your heel."

The bullet ant (paraponera clavata) (Photo by Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0)

What is actually the purpose of pain? Pain can be very unpleasant and says "let me go!" but nothing more. It doesn't necessarily mean damage through toxicity. Clever predators would learn that a colony of calorie-rich insects did not actually possess an effective defence. This led to insects evolving toxicity in order to live in large numbers and reap the according benefits. With the evolution of toxicity, pain became not just a sensation but a real weapon.

Thanks for reading! If you found this post interesting then please don't forget to show your support! :)

Deutsch

Das Wetter wird besser und ich siehe immer mehr Insekte. Die Larven von Bienen, Wespen und Ameisen sind aufgewachsen, und die Erwachsene benutzen ihre freie Zeit um Zucker zu finden. Es erinnert mich an eine sehr interessante wissenschaftliche Untersuchung: der Schmerz von Insektenstichen.

Ein Stich ist keine angenehme Erfahrung, egal ob Biene, Wespe, oder Ameise. Die Ordnung von diesen Insekten - Hymenoptera - ist eine große Familie, mit etwa 156.000 Arten. Gilt der normalen Ausdruck "Autsch" für jede Dame? (Der Stachel ist eigentlich ein modifiziertes Legerohr - also, männliche Bienen, Wespen und Ameisen können nicht stechen.)

Justin O. Schmidt, ein Amerikanischer Insektenforscher, wollte die Antwort zu dieser Frage finden. In einem Labor ist es nicht kompliziert herauszufinden, wie giftig ein Stich ist, aber Gefahr und Schmerz sind nicht dasselbe. Wie kann man Schmerz messen? Es gab nur eine Lösung: Schmidt ließ sich von zahlreichen Insekten gestochen zu werden. Das Schmidt-Stichschmerz-Index ist ein wunderbares Verzeichnis seiner Erfahrungen, und besteht aus einer Skala von vier Stufen von 1 bis 4. Insekten ohne ein schmerzhaften Stich haben keine Erwähnung im Verzeichnis.

Was einem besonders auffällig ist, sind die Beschreibungen, die oft poetisch und komisch sind. Schmidt wäre ein guter Weinkritiker gewesen. Bei Nummer 1 sind Blutbienen und Furchenbienen:

"Leicht, flüchtig, fast fruchtig. Als ob ein winziger Funke ein einziges Haar auf dem Arm ansengt."

Es ist eigentlich ein bisschen wie Noten in der Schule - je höherer die Nummer, desto schlimmerer die Schmerzen. Bei 1.2 liegt Feuerameisen:

"Scharf, plötzlich, etwas beunruhigend. Als ob man über einen Flokatiteppich läuft, sich statisch auflädt und einen elektrischen Schlag bekommt."

Bei 2 ist der Maßstab, der wir alle wahrscheinlich kennen: die Honigbiene:

"Wie ein abgebrochener Streichholzkopf, der auf deiner Haut abbrennt."

Ich habe ein Gespräch mit Schmidt gesehen - er sagt dass Honigbienen besonders gefährlich sind - weil es einfach so viele von ihnen in einem Bienenvolk geben kann.

Bei zwei liegen die Mehrheit von stechenden Insekten. Es wird stärker bei drei. In dieser Kategorie sind Insekten wie die Ameisenwespe und die rote Feldwespe.

"Ätzend, brennend und unerbittlich. Als ob jemand einen Bohrer benutzt, um einen eingewachsenen Zehennagel freizulegen oder man einen Becher mit Salzsäure über eine Schnittwunde schüttet."

Es wird besonders interessant bei den Insekten bei 4. Der Tarantulafalke ist bewaffnet mit einem 7 mm Stachel. Über diese Wespe schreibt Schmidt:

"Heftig, blendend, furchtbar elektrisch. Als ob jemand einen laufenden Haartrockner in dein Schaumbad fallen lässt."

Und der schlimmste Stich? Dieser Preis gehört zum 24-Stunden-Ameise, und der Name stammt aus wie lang die Schmerzen dauern. Auf Englisch heißt diese Ameise die Gewehrkugelameise, weil ein Stich fühlt als man von einer Gewehrkugel getroffen würde. Diese Ameise hat sein eigenes Kapitel im Buch von Schmidt. Er schreibt:

"Reiner, intensiver, strahlender Schmerz. Als ob man über glühende Kohlen läuft und dabei einen sieben Zentimeter langen rostigen Nagel in der Ferse stecken hat."

Die 24-Stunden-Ameise bekommt 4+

Was ist eigentlich der Zweck von Schmerz? Schmerz kann sehr unangenehm sein und sagt "lass mich los", aber nicht mehr. Echmidt r heißt nicht Beschädigung durch Giftigkeit. Kluge Raubtiere würde lernen, dass eine kalorienreiche Kolonie von Insekten keine effektive Verteidigung hätte. Dies führte dazu, dass Insekten Giftigkeit evolviert haben, um in einer Kolonie leben zu können und von den entsprechenden Vorteilen zu gewinnen. Bei der Evolvierung von Giftigkeit wurde Schmerz nicht nur ein Gefühl, sondern eine echte Waffe.

Danke fürs Lesen! :)

Brilliant. I read this to my 13-year-old son and it kept his interest, which is usually small as a gnat.

Hi Nikki, that's great! Dr. Schmidt has a book on this subject - The Sting of the Wild. Could be worth getting if your son has a taste for biology? :)

scary.. Got sei dank, dass ich in der Mitteleuropa lebe! :-)

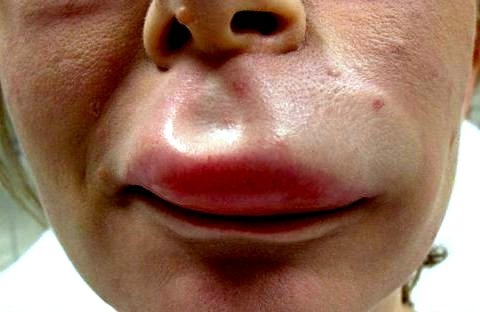

I hated the grandchildren it made me swollen

Ouch! That looks very sore! Was that bees by any chance?

Yes! Is it

Very interesting. I love Justin O. Schmidt's description of the pain. I know it was an ex[experiment, so he probably was bitten or stung in the same area. But, thinking back to when I have been stung, it occurred to me that certain areas of the body are more sensitive to pain. The most painful sting I ever received was to the roof of my mouth.

There was a bee in my Pepsi, when I took a sip. The bee wasn't happy and displayed her displeasure by stinging the roof of my mouth.

Ouch! I've only ever been stung by a honey bee (and it was entirely my own fault), and I've never been stung by a wasp. I'm guessing you aren't allergic? Otherwise that could have been very serious.

I'm not sure exactly which insect he uses - I think it might be the honey bee - but Schmidt does actually write about testing different parts of the body and which is the most painful location...I'm pretty sure the mouth was high up in that list.

Yes, thankfully, I am not allergic.