The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously once said that "If a lion could speak, we could not understand him." It's a somewhat odd claim, but it makes sense- to quote Wittgenstein again, "Shared human behaviour is the system of reference by means of which we interpret an unknown language." We lack that shared system of reference with lions. Even were a lion able to talk, it would have a completely different relationship to the words than we would. The lion essentially lives in a different world than we do- one dominated by it having four legs, being a meat eater, having a very different social structure to ours, not caring about plants like we would, etc, etc. The lion's world can be referred to as its umwelt. *While umwelt literally translated from German means "surroundings" or "environment", it really discusses the relationship between the observer and its environment. So if a lion's umwelt makes its speech incomprehensible, what would an alien's umwelt mean for communication?

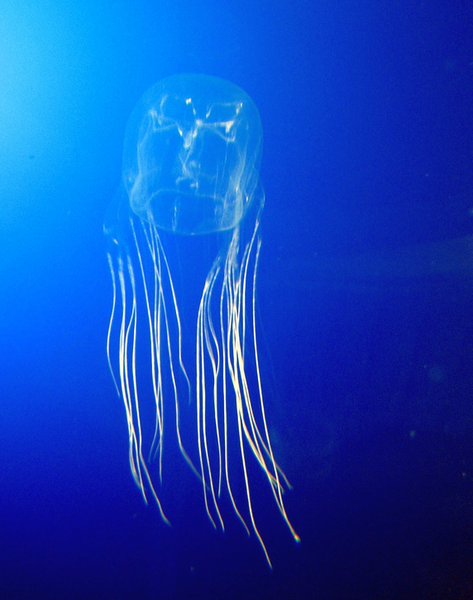

Before we try to answer that question, let's talk about cnidarians. Cnidarians- the group of animals that include most jellyfish- are in many respects the most alien creatures on our world. They lack centralized nervous systems, and instead have neural tissue distributed throughout their bodies. They can in no regards be claimed to be among the geniuses of the animal world. In fact, they shouldn't actually be able to run their relatively complex sensory apparatus with as little neural tissue as they do. Some species of sea jellies, such as the box jellyfish, have up to 24 separate eyes, which would take an immense amount of brain processing power to run. How do they do it? Well, they actually use each eye for a different purpose. Some eyes look for obstacles, others look for predators, others look for prey. The neurons they're attached to are only used for handling that specific task- they're highly specialized.

This isn't the only oddity in cnidarian cognitive function, either- their neurons are highly distributed and reprogrammed. In the 50s, a (very unethical by today's standards) scientist took to cutting apart jellyfish into still-connected ribbons without killing them. He found that the jellyfish could actually reprogram the remaining neural connections in order to transmit information along their new paths. This level of neural plasticity is certainly unusual.

Box jellyfish are much more active swimmers than most sea jellies, and as such their twenty-four eyes come in handy in steering and navigating through the water. [Image source]

So what lessons do cnidarians have to teach us in regards to aliens? Well, first off, the multiple sets of specialized eyes indicate that animals might actually have multiple overlapping umwelts of their own. This seems self-contradicting- an umwelt is, by definition, all-encompassing. Due to the lack of a central nervous system in cnidarians, it's really hard to say whether it actually possesses a central self that could have an umwelt- instead, each sensory processing system might have its own unique umwelt. It would certainly be interesting, to have a sentient extraterrestrial species with as many widespread umwelts as cnidarians- though it's hard to imagine them achieving technological civilization this way.

Some philosophers deny humans have an umwelt, and that we're the only animals capable of dwelling in the world as it is due to language and reason. This does seem to go against much of the existing animal cognitive research, however. Let's take a look at gibbons really quick. Gibbons were long thought to be much less intelligent than other apes, until one researcher had a surprisingly simple insight. Most of the intelligence tests the gibbons were put through involved picking up objects off the ground, the same as other apes. Gibbons, however, have hands that are poorly suited to picking up objects on the ground or other flat surfaces- they're much more dedicated tree dwellers than we are, so their hand behave more like hooks. When the tests were adjusted for gibbon hands, they immediately started scoring much, much higher than they had been. The tests themselves had been designed with the human hand in mind, at least subconsciously. The researchers had been testing for similarity to our hand as much as they had been for intelligence- a fairly clear indication that we do, in fact, have an umwelt.

Gibbons brachiate- travel through trees- faster and with more agility than any other non-flying mammal. As such, their hands are perfect for that, but poorly adapted towards picking objects up off a flat surface. [Image source]

This goes even farther. There are increasingly vigorous debates revolving around our definition of intelligence right now- a great many researchers think that the definitions are currently far too restrictive and narrow. One of the major divides in cognitive research is between biologists specializing in cognitive research and linguists- the biologists are more likely to be accepting of broader definitions of intelligence, while the linguists think that language is the sign or even cause of intelligence. I tend to err more towards the side of the biologists- we're quite outpaced by other species in some ways. Chimpanzees, for instance, have far better short term memory than we do- they can perfectly remember long sequences of shapes flashed briefly before them in a way that would be impossible for most humans.

Using the various examples that I have so far, I think I've adequately illustrated that aliens might be extensively mentally different than us due to their physical and neurological morphology. It somewhat beggars the imagination to think that a narrow, human centered definition of intelligence would adequately encompass any technological extraterrestrial civilizations we encounter. How, then, does Wittgenstein's claim about lions apply to beings that are literally far more alien?

Bottlenose dolphins have the second highest encephalization ratio (brain mass proportional to body mass) of any living species- second only to humans. [Image source]

One of the best ways to discuss this is by discussing much less alien creatures- dolphins. Dolphins seem to have 'words' in a quite exact sense- sounds that stand for ideas, such as fish. This isn't any great achievement, really. Meerkats have words for danger, food, etc. Parrots have names. The list goes on. Dolphins do, however, seem to use their words in a more complex, structured way. We've still had huge difficulty understanding them, however. There are some practical reasons for this, of course. For a long time we were only trying to translate the segments of dolphin speech in our hearing range, but dolphins can produce sound in far greater ranges than us, including using their sonar. Dolphins also have much, much thicker neurons than us, meaning they think much faster, whether or not they're as intelligent as we are. So much of the early research into dolphin communication is flawed in that it tries to parse dolphin song and calls at human speeds, rather than slowing it down.

It should also be noted that dolphins are very much as curious about us as we are about them- they're certainly trying to communicate with us as well, though (despite what hippies will tell you) they're definitely not as smart as we are- at least on our scale of intelligence. (Here's where we have to balance between allowing for more divergent types of intelligence than we've had in the past and allowing for so many different sorts that we can't compare them.) Our language is far more complex than theirs, so far as we can tell- noting, of course, that many researchers, especially linguists, will point to our failures to translate dolphin language as strong proof of its absence. To bring a bit of pessimism into this discussion, if dolphins and us are both working to communicate with one another and yet still failing, what odds does that give us to speak with a truly alien organism?

Mnemiopsis leidi, the sea walnut, scourge of the Black Sea. While it looks like a jellyfish- a cnidarian- it's actually a ctenophore. [Image source]

Before we go, however, there's one more type of animal I'd like to bring up- the ctenophore, or comb jelly. Ctenophores are easily confused with cnidarians- they look very similar, just lumps of jelly floating through the oceans. They're very, very far away on the evolutionary tree, however- they actually split away before the evolution of nervous systems. And yet, they have nervous systems of their own- completely unrelated to ours, or jellyfish, or octopi, or dolphins. They evolved their nervous system completely separately, using a whole different set of neurotransmitters and other chemical building blocks in one of the most stunning cases of convergent evolution in our planet's history. Nervous systems weren't a one time fluke, and if we find other life out there, well, the odds just went way up that some of it is intelligence. It makes the universe feel a little less lonely.

Bibliography:

- Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, by Frans De Waal

- Spineless: The Science of Jellyfish and the Art of Growing a Backbone

- *Voices in the Ocean: A Journey into the Wild and Haunting World of Dolphins

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umwelt

- https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/b/budiansky-lion.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2003/jul/03/research.science

- https://aeon.co/essays/what-the-ctenophore-says-about-the-evolution-of-intelligence

You received a 80.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "ecology".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

That's odd. Did we have this ability and lost it, or did chimps evolve it separately? I've watched apes choosing shapes in vids and they're quite good at it and fast. I can understand other animals doing better at tasks that I would deem "physical", but this looks like the kind of thing humans should be good at.

A good blend of science and philosophy, this post.

An entirely speculative theory of mine is that it's correlated with our significantly weaker senses of smell- given that smell is the sense most strongly correlated with memory in hominid populations. People in hunter gatherer tribes tend to have much better senses of smell and better memories. Chimps have much better senses of smell yet. Of course, there's also the whole "writing degrading memory" theory to reckon with as well.

And thanks, glad you enjoyed it!

I'm liking this new series @mountainwashere. I love posts that teach me something new as a biologist. The idea of multiple umwelts is certainly an interesting one, particularly in cases of creatures which theoretically can't integrate the different inputs into one, cohesive 'vision' (as we would see it). The really interesting question is whether this then generates a cognitive barrier to developing higher intelligence as the functioning of these types of animals is far more like an automaton (in the same sense that insects are - functioning largely on a set of stimulus-response functions). Thought provoking stuff!

Thanks! The idea of multiple umwelts is actually a slightly contentious one, at least between me and my buddy I discuss philosophy with- he holds forth that for any given organism there is only one umwelt, regardless of things like whether it integrates its sensory input or even if the organism is actually a colony organism like a siphonophore, where every organ is actually a different critter all working together. He even holds that an anthill only has a single umwelt, which is actually somewhat mainstream in umwelt related thinking.

Of course, umwelt as a concept is nearly 80 years old, and it starts to break down when it comes in contact with taxonomic questions. Actually defining what the boundaries to a species or a particular organism can somewhat break down some of the underlying assumptions of umwelt.

As for whether non-integrated sensory input would function as a cognitive barrier- I personally think that it depends on the degree of non-integration. If it has a central nervous system analogue that integrates at least some of the input, I think it could achieve higher intelligence even if a great deal of its sensory data isn't integrated. If it's unintegrated to the degree that box jellies are, I'm pretty doubtful.

I touched on the umwelt concept during some research I was doing for my Masters but didn't give much thought back then to how it would apply to colony organisms like ants. I still see organisms like that as having an individual umwelt however, as there is still sensory information they share among themselves regarding the location of resources etc. To my mind, the concept of a shared umwelt would imply each individual is at all times aware of all aspects of the colony which, of course, isn't the case. It's an interesting concept to play with though. There are so many questions in cognitive fields which are exceptionally difficult to realistically answer though. One thing I've always been fascinated by is episodic-like memory which is also exceptionally difficult to prove in animals - I.e. Separating out general associations with a particular object say from recall of a specific event involving that object. I wonder whether we'll ever find a way to address these types of questions?

It's entirely possible we'll find a way to tap into animal brains and read their thoughts someday (terrifying implications for human society going along with that), so perhaps we'll know the answers- but my gut instinct is that we're a long, long way from answering those questions. I think we're still very much in the early days of science in some regards.

Definitely still early days - interestingly one of my animal behaviour profs back in the day reckoned that once we can read animal thoughts we may not find what they have to 'say' all that interesting. As someone who studies behaviour for a living, seeing them do the same exact things day after day, I think she may have a point. But I reckon we're in for some surprises with the likes of dolphins and Cephalopods though :)

Man gains ability to read Dog's thoughts. All Dog things is "arf."

Lol, well from what I've seen of bat eared foxes I'd be expecting something like: Termites? Termites! .....ooh, more termites! More or less on an infinite loop... 😂

Yes, I was going to say, we use language to individuate organisms, and then give an umwelt to each of them, so it would seem that language predates umweltification :P

My "theory of use" is much more inclusive and rational and scientific, I think: There are objective stuff out there. We view only those parts of the stuff that are important to us. So for example I'll view a woman as a sexual object, the lion will view her as a meal, and if we view the object (woman) in only those ways, then it's impossible for me to communicate with the lion, even though we are referring to the same object. And then some philosophers will start talking about how everything is therefore subjective and there's no real objects out there except for what we see, which disappears as soon as we stop looking. To me, it doesn't matter whether we exist or not: the real objective object is the collection of all its possible uses (meal, partner, mother, daughter, and things we never thought about). An object is the totality of possible uses. The more uses we figure out, the closer we are to seeing the object as it really is. Sans those uses, there is no object: anything that exists must be able to be used in some way. Btw, if the lion can, maybe in its hornier moments, see the woman as a sex object, and if I, in my hungrier moments, can see her as a meal, then the lion and I have understood each other.

Anyway, just wanted to give my theory of use in a nutshell! There's plenty more to it. The initial inspiration was the pragmatist maxim (which I consider pure genius), but I've deviated from that substantially since.

Philosophy... the place to go if you want to unfold your soul. :)

Thanks to provide us with this text!

Thanks for reading!

The decentralized, localized neural system of the jellyfish can theoretically generate reaction response far faster than a centrally mediated system. Could it be that the jellyfish perception/reaction frame exist on a time scale far too quick for centrally mediated neural beings to comprehend? Does localized neural system of the jellyfish allow for directed action, or would such localizes neural net be purely limited to reactions?

I like the concept of umwelt, as it suggests at the recognition of identity being tied to communal/cultural/biological matrix of a creature. If we can extrapolate the concept further, in essence, human identity is linked to the shared experience within the context of his environment. It reminds me of Thomas Sowell's observation of objective cultural superiority existing in relation to environmental and functional matrix. In destroying our world, man pollutes the matrix that defines his being, and ultimately self-annihilates not only his physical aspect, but the very conception of humanity itself.

Dolphins definitely live in a faster time scale than we do. Jellyfish do seem to have fairly fast reaction times, but they're not unbelievably fast- their nerves aren't particularly thick, which is a large component of the speed of reactions and actions. I think that the localized parts of the jellyfish nervous system largely perform reactions over actions as well.

Umwelt is right there on my short list of my most used/favorite philosophical concepts. Where exactly we draw the line of umwelt is one of the most important and useful questions it poses. With ants or bees many thinkers happily claim that a hill or hive shares a single umwelt, but where does that end? They almost universally claim we all have individual umwelts, but a town or nation having an umwelt seems entirely plausible. I'd entirely agree with your extrapolation linking human identity to shared experience. The tendency to compartmentalize and treat individuals as discreet really is a problematic facet of Western culture at times. By doing so, it's exactly as you say- we're polluting the matrix, the shared experience that is the cultural umwelt.

I've occasionally used Sowell's ideas to argue against Charles Murray's ideas, which is a particularly entertaining and somewhat perverse exercise, since I've definitely noticed some overlap in the followers of the two.

Very deep stuff and I'm learning lots, thanks. But about that Wittgenstein quote, I can't help but to disagree a little. I think we and lions could understand each other, at least some bits and pieces. We are closer to most mammals in emotions and instincts than people who defend slaughtering them want to believe. Humans like to smell each other on the temples and surrounding areas just like cats. We both sniff better when we open our mouths and wrinkle our noses. Like lions we hunt in teams, pecking order is very important, and we love the excitement of the chase. Etc there are so many examples, I wonder if Wittgenstein ever had a pet, and if he did, if he ever truly observed it. :)

I'm actually prone to agreeing with you- I think that, ultimately, we have significant capacity for comprehending the mental states and emotions of other terrestrial creatures. Wittgenstein's quote is, however, one of those ideas that does need to be confronted in related discussions.

I'm not familiar with whether Wittgenstein owned pets himself, but his comments were to a great extent representative of the general views of his time on animals. They were often thought of as mere automatons, simply reacting to stimuli, without any real emotions. It was even widely believed that they couldn't feel pain. He's actually rather enlightened in that context- he did seem to believe that they were actually capable of perception and more than merely reacting to stimuli.

I learnt lots of things from this post. While I was reading, it felt as if I was watching Discovery channel or Animal Planet. I was intrigued by the title and shortly blown away by the amount of information provided. I like the theory of multiple umwelts, it's fascinating!

Thanks!

consider the domestic housecat.

they live with humans...they share the same environment.

Do they have the same 'umwelt' that humans do?

Oh, definitely not! They have much, much keener senses of smell than we do, for instance- they essentially have access to a whole world of sensory data that we lack. They prioritize their senses in a manner entirely different than ours. Take television, for example. Most cats have little to no interest in televisions, while most humans will be well aware of what's on any TV near them. Some humans, like myself, have trouble looking away from televisions, which is a big part of why I don't own one. This difference in interest can be very much understood as a difference in our umwelts- the umwelt of the cat really has no room for the television.

All of this doesn't even bring in differences like them being four legged compared to our two legs, or the fact that they lack opposable thumbs. A jar lid is easily navigated for us, whereas it is an impossible barrier for the housecat. Ultimately, we have to understand the same dwelling place as being an entirely different habitat for a cat and a human- the manner in which the two navigate the exact same space is entirely different.

Dogs are another great example- for us they're adorable companions, for cats they are, more often than not, gigantic and terrifying predators.

I live with four cats. One of them is bonded to me. We've been together since he was a kitten. (about six years) He never leaves my side. I don't get out much and when I'm on the computer he's by my side on an end table (like now)...when I sleep he's on the bed beside me. when I go outside and sit on the patio he allows me a certain amount of time then he starts bitching.

I'm convinced that he can see things that I can not.

I'm like you regarding TV. Hate's them I do. I've not watched TV since the seventies. I can't stand to be in the same room with one.

That's adorable! I'm jealous, I just have one cat, although he's pretty cuddly.

yup

You can see from science-fiction movies that we imagine alien intelligent life would be very similar to us. It's an interesting thought experiment to imagine interplanetary life that evolved from a jellyfish. It would definitely be difficult to communicate with something with no central brain!

It'd be so difficult! We already have intense difficulty understanding other species living here on this planet.

This is incredibly detailed.

Thanks!

You have a minor misspelling in the following sentence:

It should be separately instead of seperately.Thanks, bot.

Your Post Has Been Featured on @Resteemable!

Feature any Steemit post using resteemit.com!

How It Works:

1. Take Any Steemit URL

2. Erase

https://3. Type

reGet Featured Instantly & Featured Posts are voted every 2.4hrs

Join the Curation Team Here | Vote Resteemable for Witness

Super informative and interesting information.

Wouldn’t intelligence be relative. Unless we’re strixtly talking about communication or language. If their intelligence is only intended to benefit them, maybe they have understood us enough to satisfy their needs. And thus their lack of human curiosity or need to assign a meaning or value to something is not important to them. So they may understand us in way that we haven’t evolved to comprehend. And maybe their senses are more advanced and thus they are more intelligent. Just a rambling thought on the subject of intelligence based on the comparison provided above between humans and dolphins.

Congratulations! This post has been chosen as one of the daily Whistle Stops for The STEEM Engine!

You can see your post's place along the track here: The Daily Whistle Stops, Issue # 86 (3/27/18)

The STEEM Engine is an initiative dedicated to promoting meaningful engagement across Steemit. Find out more about us and join us today!

Hi, I just followed you :-)

Follow back and we can help each other succeed!

Spam.