Totally get the fear of messing up a crypto transfer. I've double-checked addresses so many times, it's almost a ritual. One wrong digit and it's gone. Sticking to small test transactions first has saved me more than once

Nah, I haven’t sent a test transaction to the wrong address, but I’ve come close with typos. Always triple-check. If it’s wrong, the funds are usually lost unless the recipient sends them back. Test sends are my safety net

Man, losing 4 STEEM like that must sting. I've had close calls myself, which is why I’m obsessive about test transactions. One small send first, confirm it’s right, then the rest. Saves a lot of heartache

Just like on any social media site you friend someone on the blockchain.

Then, you don't have to remember if you typed their username the right way. You'll look them up on the contact list and know it's the one you friended.

Crypto never sleeps, unlike us traders trying to sneak a weekend break. Markets keep moving, and missing a key shift can hurt. Gotta stay alert, even if it’s just a quick chart check on a Sunday 😅

There comes a time in life when a man prioritizes having peace, focusing on his spiritual connection, dedicated work, and self-improvement above all else.

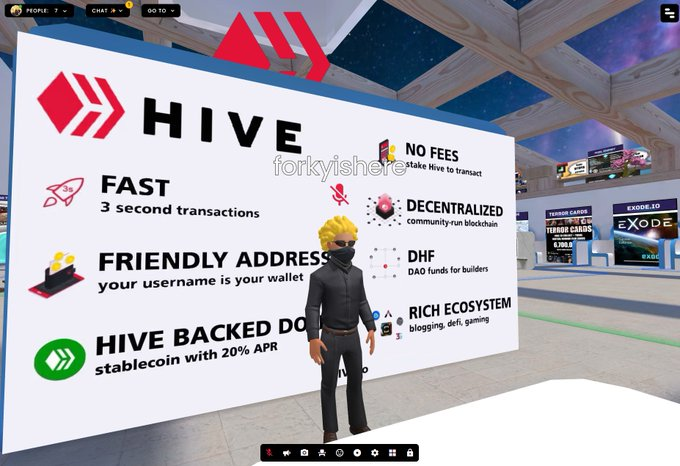

Cos it's a 100% guaranteed success, not that LSTR it's not but no volatility will affect SURGE (unless LSTR quotes over $50) since it's pegged to 1$, hence you're on a winning move buying below 1$ once the presale is finished.

I love having a 17% (maybe more) APR paid weekly and with no staking, so you have liquidity all the time.

The compound interest that you may build is commont to HBD and that's a great deal too, your savings ball becomes bigger and bigger, if you kepp periodically investing in SURGE your compound interest becomes greater sooner than expected.

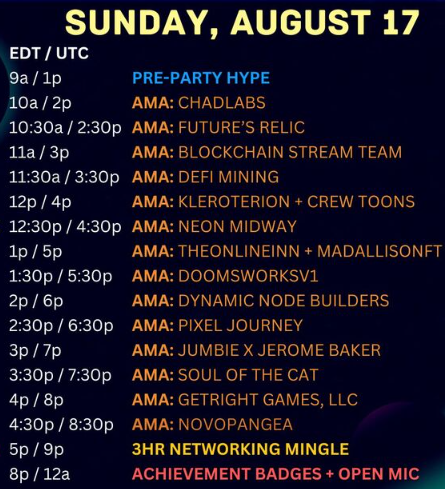

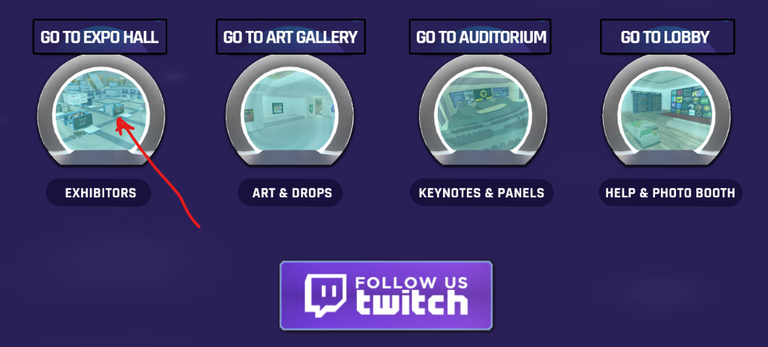

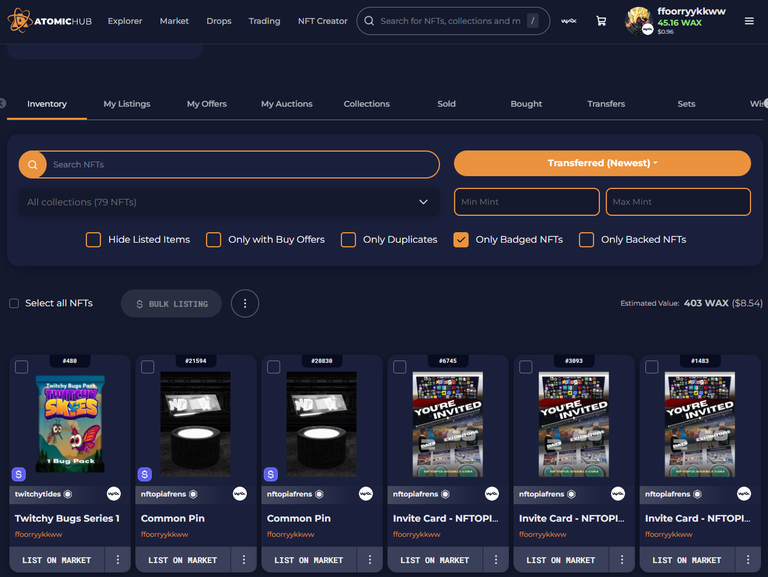

If you have a WAX address, make sure you have your wallet ready and be prepared to link some addresses to the twitch stuff, as there are plenty giveaways on these events.

I use Anchor, but you can use whatever you are most comfortable with.

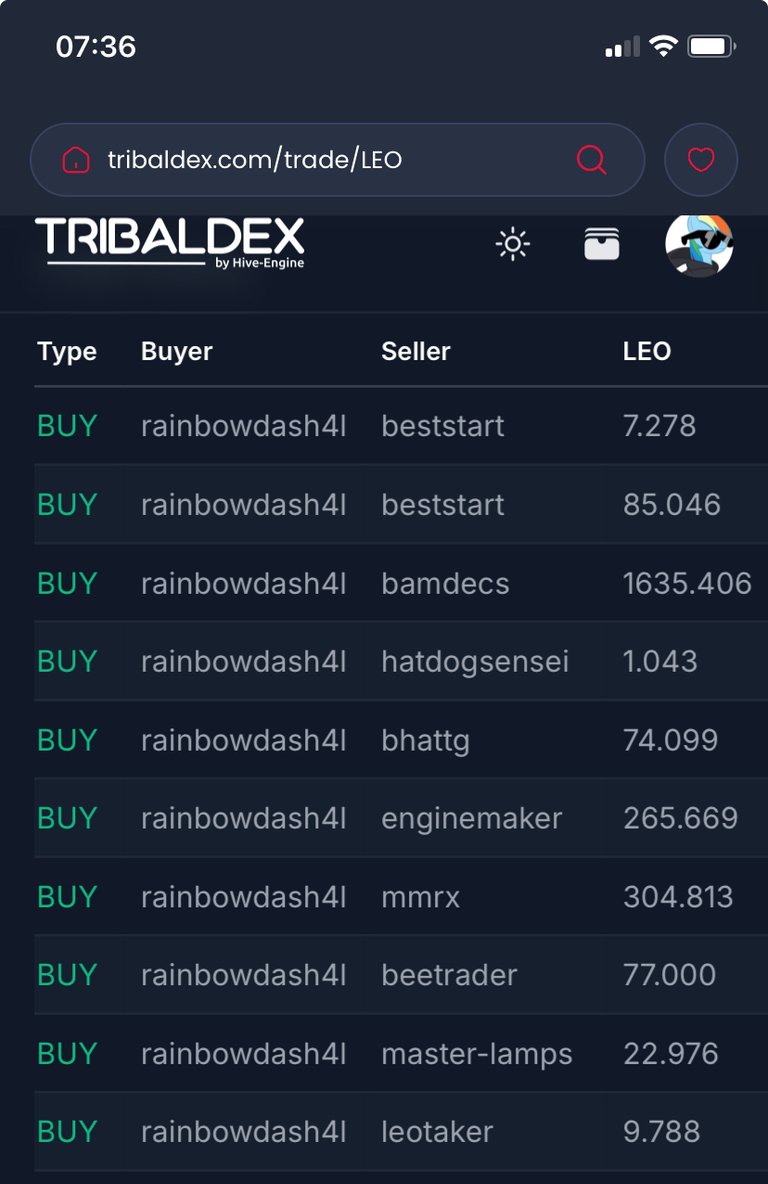

Sweet !! Just signed up using inLeo App .. pretty seamless and trying to catch up on whats new here. SURGE and all those stuff .. interesting !!! I sitll dont know how to move my LEO from Hive to the Dex though. Anyone can give a tip ?

I have on thing to ask. Now the price of SURGE is 4 $HIVE and it's below 1 dollar. But if the HIVE price increase, do I need to spend 4 HIVE for buying SURGE. In that case the price of SURGE will cross 1 dollar.

Did you hear about the guy who threw his alarm clock while hosting a party? He wanted to see if time flys while having fun. Credit: reddit @caspermoeller89, I sent you an $LOLZ on behalf of luchyl

Totally agree, having a few strong convictions and going deeper on those long-term picks is where the real gains are. Spreading too thin just dilutes the impact.

Spot on. Holding tiny fractions across hundreds of stocks often leads to higher fees and less focus. Better to build meaningful positions in a smaller, well-researched set of assets. Learned this the hard way early on

I just can't believe I forgot to go to the Gym again yesterday. That's six years in a row now. Credit: reddit @senorcoconut, I sent you an $LOLZ on behalf of ben.haase

What's up, everybody? My name is Dimitri Kofinas, and you're listening to Hidden Forces, a podcast that inspires investors, entrepreneurs, and everyday citizens to challenge consensus narratives and to learn how to think critically about the systems of power shaping our world. My guest in this week's episode is Benjamin Bratton, a professor of visual arts at UC San Diego and the author of a recently published book titled Revenge of the Real, Politics for a Post-Pandemic The book explores how our collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates a critical inability on the part of society to govern itself. The pandemic in this sense serves as a sort of non-negotiable reality check that appends the comfortable illusions of a world that increasingly bears no resemblance to the one we have vacated. It's a conversation that raises important questions about not only how we came to find ourselves in our current predicament of mask wars, urban riots, and institutional decay, but also (1/42)

how we might go about constructing a world that is more representative of reality and the needs of the present moment. This part of the discussion continues into the overtime, where Benjamin and I explore what a post-pandemic world might look like and what this means for our conceptions of governance and the individual. So without any further ado, I bring you my conversation with philosopher and author Benjamin Bratton. Benjamin Bratton, welcome to Hidden Forces. Thanks for having me. It's great having you on. So you and I have spoken briefly by phone and just now I've read your book this weekend. I think the entire framing of the book is fascinating and it touches on a lot of the topics that I've raised on prior episodes of Hidden Forces. Before we get into the book, I'd love for you to describe yourself because you're a rather eclectic guy. You seem to have, you don't fit into a box, not even close. So I'm curious how you describe yourself and what are your interests? What drives (2/42)

you? Well, to admit, I sometimes have a hard time describing myself in this sense. I suppose really I'm a writer. I write a number of books of nonfiction, primarily focused on issues of philosophy, computer science, design and architecture, geopolitics, various mixtures of these. So kind of depending on the audience, different things come to the fore. I'm a professor at University of California, San Diego. I also taught at Syark in Los Angeles. I direct an urban futures think tank at the Strelka Institute. In Moscow, the current iteration of which is called the terraforming, which is not the terraforming of Mars or the moon to make them suitable for earth-like life, but rather the terraforming of the earth to ensure that it remains viable for earth-like life. The new book that you mentioned that comes out this week is about the pandemic and what happened, what we need to learn from it, what was exposed in essence, how to make sense of it. So what led you to write the book? Was it the (3/42)

pandemic or was the subject brewing in your head long before that? Yeah, probably just some extent. I mean, the book really is a book of political philosophy more than a kind of policy blueprint. The book emerged from an essay that was published quite relatively early in the pandemic in March or April called 18 Lessons of Quarantine Urbanism. And I suppose in terms of what led me to write it, I think a lot of us who have friends and colleagues in China were watching what was happening and felt a little bit of a Cassandra complex that we knew what was coming. We were watching the administrations and maybe our friends and colleagues sort of sitting on their hands and various things sort of had come to pass. And so it became clear to me that in many regards that instead of thinking of the pandemic simply as a kind of state of exception and aberration from the norm, it really was a kind of episode by which a number of let's say pre-existing conditions were exposed, kind of added old adage (4/42)

of when the tide goes out, we can see who was swimming naked. And it turns out it was not just a few people, but in many respects, an entire system of healthcare, an entire logic within philosophy, an entire logic of biopolitical critique that ended up being enormously unhelpful in thinking through what the pandemic was, what our responses might be. And perhaps on the most deepest level, a kind of crisis in the logic and culture of governance, particularly in the West, that among the most richest and technologically sophisticated countries in the world were found themselves basically helpless for reasons that were unnecessary and should hopefully never be repeated. So how much of this book is a critique of Western political culture and what you termed to be its philosophical shortcomings? And how much of it also applies to Eastern Asian countries, some of which perhaps did much better under lockdown? Well, to some extent, I think it would be a mistake to make two gross generalizations. (5/42)

Clearly, the country, I mean, the way I put it is like this. One of the ways to think about the pandemic was that we all sort of lived through involuntarily, the largest control experiment in comparative governance that we're likely to see. The virus was the control variable and different policy regimes, but also different political cultures were tested. And the results are plain to see. Can we measure deaths per 100,000 and any number of other things you may wish to look at? And the countries that did the best, perhaps Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, some others, are Asian technocracies that were able to respond quickly, partially because they had experiences with SARS because they had a kind of equitable, inclusive, and effective public health institutions. And they have a kind of political culture that is well suited to a capacity for collective self-organization. And quite clearly, certain kinds of policy decisions and policy instruments that were deployed in Taiwan, for example, (6/42)

simply wouldn't have been culturally possible in Texas or Southern Italy or Brazil or Italy. And that if the Asian technocracies, to a certain extent, may have done well, and I'm not in any respect trying to gloss over the problems in China's response, for example, but the countries that did the worst were clearly the ones that were run by the wave of populist regimes that had taken power over the last decade, United States, Brazil, India, I've mentioned, the UK, Russia. And that one of the lessons to be drawn from this, which should have been obvious, is that populist politics emphasis on narrative, on cultural narrative, the idea that a constructed narrative as a way of understanding how the world works, how political power might be organized, simply doesn't work. That ultimately, an underlying reality, a biological reality, a biochemical reality, an epidemiological reality that is indifferent to social construction will ultimately have its day. And I think that's what we saw. How (7/42)

much of the impediments that were erected, let's say, by populist regimes, were the result of cultural factors? And how much were simply the fact that these regimes or these administrations or candidates came to power by directly delegitimizing or pointing to the inefficiencies or corruptions of the existing institutions, and that therefore, in their response, it was very difficult to consistently corral the population to follow the administered line? That's right. It's a vicious circle in the logic of populism. And you may say that there's a kind of... I mean, the way I would see it is that over the last generation or so, 40 years, there has been a... From the beginning of neoliberalism, there has been a kind of deliberate dismantling and deconstruction of the principle of governance, both on the right and on the left, as a kind of something that should be seen with a kind of permanent suspicion. This dismantling of governance makes governance ineffective. That governance becomes (8/42)

ineffective, governance becomes delegitimized. That governance becomes delegitimized. This gives, as you suggest, oxygen to populism of all sorts. The dysfunction of government is in and of itself an excuse for further delegitimization and deconstruction of the systems of government, which then make it even more dysfunctional, which increase... It's a vicious cycle. Yeah. More vicious than virtuous. That's right. That's right. And so you end up with the situation in which with populations that are for both legitimate and probably illegitimate reasons are less able to collectively self-organize, find themselves in a situation where that collective self-organization is impossible and we have body count to prove it. So I'm curious. I mean, you're touching on it and we'll get into it later in the conversation as well. Where did the title of the book come from? Can you speak a little bit more to what you mean? The Revenge of the Real. Right. When you talk about the real. Well, the real is, (9/42)

as I say, is that kind of underlying biological, physical, material, epidemiological reality that is indifferent to cultural projection, indifferent to social construction, indifferent to our narrativizations. We are part of it. It's us. But whether we're talking about a pandemic, we're talking about climate change, we're talking about any number of ways in which the underlying biochemistry of our planetary condition is, in essence, bursting through the seams of the narrative illusions that we all try to use to make sense of the world around us. This suppression of the real, which is again is, I think, central to this project, can only last for so long. And that the law, you know, when you think of it sort of a boiling pot, the more that it is suppressed, the more that it is ignored, the more that our preferred illusions take up the time and space that should be used to kind of address the world as it is, the more damaging and the more violent that eruption actually is. So besides (10/42)

COVID-19 or infectious disease, what are some of the other forms of the real that the pandemic has forced us to confront? And how important is the fear of death and our societies, I think, really unhealthy relationship to mortality? How does that factor into all of this? And I'm reminded of the experience of the United States of the citizenry to the attacks of 9-11. And without minimizing how scary those attacks were, I also want to emphasize that I think our reaction to them was exaggerated. And it was, in some ways, a reaction that was politically beneficial for the administration at the time, which stoked fears and concerns. But people also did have an exaggerated fear of death, death, something which is inevitable and which we all will face at one point or another. And then all we can do is prolong it for a very short period of time and get people are willing to go to great lengths to forestall or perhaps even in their head, if they can imagine it, prevent it entirely. So how did (11/42)

this pandemic bring out our fears around mortality and morbidity? Well, it's a fascinating question. I think that in terms of linking with 9-11, which is an interesting one, I suppose the way in which I might approach it has to do with the ways in which we understand where risk really is and what really is a risk, what really is something that may result in our death, which is something that might be dangerous to us. And what, on the other hand, is something in which we invest and organize our fear of death. And these are not always the same thing. I think to your point, obviously, in the years after 9-11, the question of trying to reorganize our society and reorganize our cities, reorganize our airports, reorganize our schools in relationship to the threat of political terrorism became a national project. It was a refortification against a presumed and predictive and possible speculative future violence, one that was extraordinarily unlikely compared to, for example, dying of heart (12/42)

disease, dying of lung cancer, dying of any of the kinds of things that Americans tend to die of, diabetes and so forth and so on. And so there is a sense of risk, and then there's a sense of where a place where risk is actually invested. I think with the pandemic, this kind of miscalculation of risk that we saw that was probably most pervasive was not the kind of being afraid of shark attacks kind of risk that we saw after 9-11 where there was a kind of, all of our attention on the wrong thing. It was more about a miscalculation of the relationship between individual risk and collective risk. And I think this was kind of the last of the pandemic. One of the things that the pandemic showed was that many of the risks that any of us may face personally are really our collective risks, that if someone in my city is infected, is sick, or if several people in my city are infected or sick, that this is a risk to me. And that my investment in care for them, my investment in testing for them, (13/42)

my investment in the provision of appropriate healthcare for them is to my benefit. There was a meme going around, around sort of in the middle of the culture war over masks that was about someone who refused to turn on their headlights as they were driving around the city because they could see everybody else. They have the freedom to drive their car on the road so forth and so on. I think that part of the culture war over the mask was where this issue of risk really became and the kind of calculations and miscalculations of risk really came to bear. So this is an interesting part of the book where you couch this observation in terms of the subject versus object as well as our over-individuation. Explain to me what you mean by that. How does our conception of the immunological commons and our conception of individuality interface with the realities of the world and the fact that so many of the risks we face are communal as opposed to individual? I mean, they affect us individually, (14/42)

but they are macro risks. That's right. Well, one of the things I talk about is what I call the ethics of the object, which we might contrast to an ethics of the subject. In political ethics or really ethics more broadly, there is a presumption that one's subjectivity is the basis of this ethical discussion. Put simply, if I can calibrate my internal moral state, my sort of mental disposition towards you or to the world in a particular kind of way and train this and discipline this towards the proper ethical disposition, then my activities, my behaviors and the effects of my activities and behaviors will be somehow correspondent to this internal moral state. If I think good thoughts, I will do good things. If I do good things, then good things will happen. Intentions matter, in other words. Intentions not only matter, intentions are the thing that matters. The focus for ethics is on the calibration of intentionality. That's what I would say is the inherited sense of ethics of the (15/42)

subject. By contrast, what I suggest is the ethics of the object that must be added to this, not necessarily replace it, but added to this. The reason we wore masks was because we came to a different kind of ethical realization, whether we realized it or not. When I approach a stranger in the street, we're both wearing a mask, the possibility that I might infect them, do them harm, do them a kind of potentially serious form of violence, has nothing to do with whether or not I like them or hate them or know them or don't know them or have. My internal subjective moral state towards this person is totally irrelevant to whether or not my actions will do them harm. My actions will do them harm because of an objective biological reality that we are part of the same species, that there is a virus that my exhale is their inhale and so forth. We wore masks because we were able to recalibrate a logic of ethics towards one's self as an object, one's self as a biological object, and to construct (16/42)

a kind of public ethics around this reality. We were able to do it relatively quickly and to activate this relatively quickly. This too, I think, is one of the positive lessons from the sociologic of the pandemic. Not that I think we should all continue to wear masks forever and ever, but more generally, this sense of understanding ourselves in relationship to the world through this lens of the objective, to think of the objective as a space of ethics rather than as a kind of space of over-rationalizing tyranny against ethics is, in fact, something that's very important. So how much of this reflects an evolved understanding of ethics in your view? And how much of it is actually a result of fundamentally new dynamics on the planet as a result of not just population changes, but also changing ecosystems as a result of some of those population changes and practices, etc. How much is the ethics of the object? How much is the pandemic itself? No, not the pandemic itself. How much is the (17/42)

ethics of the object on evolved understanding? And how much of it is not so much an evolved understanding? You could still say it's an evolved understanding, but the circumstances of the earth and of human society on planet earth are different than they were a thousand years ago. Where there are more people, we have different types of technologies, different types of wastes, different types of problems. That's right. So how much of this is a philosophy for the current age? Well, I think it is a philosophy of the current age, but I think that if it is an evolved understanding, it is an evolved understanding of a condition and circumstance that in a way always has been. We always have been a kind of biological creature. Unwitting agents in all sorts of harmful dramas. Unwitting agents, exactly. Unwitting agents, unconscious objects in a certain kind of degree. The way in which I would couch this in a bigger picture, and I'm not sure the ethics of the object would qualify of this, but (18/42)

this kind of what you call a kind of evolved perspective. Another way of putting that might be in relationship to what I call in some other work, the Copernican Trauma or Copernican Turn. There are moments in, and this goes to your question about the technological aspect of this. There's moments in history, in sort of socio-technical history where we use technology in a certain way that allows us not just to do something in the world, but to discover that the world works very differently than we thought, the technology that we use to make it. So a telescope or a microscope, without telescopes, a heliocentric cosmology isn't really possible. Without microscopes, don't cause microbes, but once you understand that the surfaces of the world are covered with them, you see them differently. I think Darwinian biology was a kind of Copernican Trauma, neuroscience by which we understand ourselves as an animal that our most beautiful forms of cognition are also animal forms. Neuroscience, where (19/42)

our thinking about our thinking and understanding that to itself as a physical objective fact, this is marvelous. I think artificial intelligence and what I call synthetic intelligence will also prove to be a kind of Copernican Trauma, but there are a number of different sequences along the way by which we come to understand, in essence, the objectivity of our subjectivity in ways that change the way we understand the world. Most of them, most of them were able to be accomplished through some form of technological abstraction and alienation. The technology was essential to these kinds of epistemological transformations. To that point, let's reverse that a bit. How much is our subjective notion of self and personal identity formed by similar types of models and frameworks that we bring to the world? Well, this is a big question to the extent to what sense of our sense of self is part of a neuroanatomical disposition. Exactly, right. That agreeing to structural language and process (20/42)

lights and sounds in particular kinds of ways, all those, you can't separate a sense of self from that. Those things are themselves not givens. They are the result. I would make this point. We have always been technological creatures in a certain sense, and that even our anatomy itself is the result and effects of millions of years of technological mediation with the world. We have opposable thumbs, not so that we can pick up tools, but because our ancestors picked up tools. Our thumbs work the way that we do. This question of to what extent are we a biological given that then enters into social relations and mediations with the world, and to what extent do those mediations and social relations with the world produce that biological condition is a bit of a, I would say, chicken or egg situation, though obviously, we know that eggs came before chickens by several million years, so it doesn't really hold. It's a dynamic process, in other words, that our conceptions of the world and our (21/42)

biologies, those are constantly evolving. But what I'm trying to wean out though here is that, yes, our sensory perceptions allow our individual beings to process information individually, but that's not the same thing. Right, but that's not the same thing as our conception of self and our sense of identity and ego. That's right. So how much of that would you say is kind of running as a piece of software as opposed to being hardwired in a biology, that if a different type of culture existed in the world, that you could take the same biologically evolved human beings, but those individuals could operate in a world where with far less ego, far less sense of self. I mean, there are all sorts of theories, one of them, obviously, I think generally discredited from the 1970s, Jillian James' bicameral mind, but that posited that the ancients actually had far less or lacked an ego entirely and had a relationship to the gods that was really a sort of an expression of their internal bicamerality (22/42)

between their conscious and unconscious mind. So that's kind of what I'm getting at, which is it seems to me when I read your book that what you're suggesting is that given the state of the world, given where our technology's at, etc., etc., part of what the solution means is moving to a world where we think of ourselves less as individuals and more as part of a collective. And so what does that mean experientially and qualitatively for a human being living in the world? Yeah, thanks for the question. Let me put it this way. There are a lot of ways in which one might experience one's own subjectivity, one's own agency, one's own identity. I think we are at a sort of weird cultural moments in the West where all three of these things are thought of as basically being more or less the same thing and they're not. And so if one has a sense that one's agency is insufficient, one might choose to amplify one's sense of identity or subjectivity. And I think in ways that we could go into, this (23/42)

has led to a number of problems, including the populist wave that I was speaking to. Now to your question about the hardware software aspect of this, which is a kind of interesting one, we think through many as homo sapiens, we think linguistically, we think visually, of course, we think auditorially, we think in lots of different ways, but language both spoken and written in the last several tens of thousands of years has become an increasingly central part of how it is that we think language itself is obviously deeply social and trans individual at its foundations. For me to even think about my own, you know, independence and autonomy, I'm thinking about this through the grammars and structures of a language that is already trans individual. And so the conditions of that sense of subjectivity, that's not the same thing as autonomy, but let's say that sense of autonomy is itself constructed through a non autonomous technology. I don't know that this is a paradox, but it is certainly (24/42)

an important way to appreciate this. You know, in terms of consciousness, which is something that I know a lot of people are very concerned about, I happen to be particularly in my recent work around AI and synthetic intelligence, I've become less focused and interested in consciousness per se. But it's a neuroscientist at Princeton named Graziano, whose work on the social theory of consciousness I find rather compelling. And basically his idea goes like this, is that in all predator-prey relationships, there was some kind of capacity for other mind projection, that the fox can imagine how the eagle sees. And so it knows to go under and hide because it's imagining a line of sight from above or to catch a fox, you need to think like a fox in this way. So there's some kind of undermined capacity to anticipate what the other person's thinking. What's happened is that one of the things that makes our sapiens, whatever, 60,000, 40,000, where we want to sort of locate this, we're able to in (25/42)

essence turn that other mind capacity back in on ourselves. We were able to think of ourselves as if we were an other mind, as if we were an external kind of structure. And it's this interiorization of what began as an exterior relationship to the world that probably took a great lesson in the basis of this sense of subjectivity in the first place. I don't fully follow that last part. First of all, what are we talking about when we say consciousness number one? And where you lost me was in the turning consciousness in on itself, that somehow the human version of consciousness or expression of it is somehow different than that of, let's say, a predator or a prey. It is. I mean, I'm sorry. I didn't mean to make it obscure. That's fine. But so yeah, first of all, what do we mean when we talk about consciousness and then what is that distinction? So consciousness in this sense would be this experience of one's own, this sort of subjective experiences of one's own thoughts. So thinking (26/42)

about thinking, let's say, the capacity to not only think anthropocriticities, but to think about thinking and perhaps to think about thinking about thinking in these terms of this. A larger sense of cosmic awareness? Well, a larger sense of a kind of reflexive awareness of one's own sentience. Like we might separate sentience from sapience in this regard. Yeah, because I wouldn't necessarily connect consciousness with ego or identity, which is where I think I'm getting a little confused. Are you putting those two together? No, I'm not. I was suggesting that since you were talking, we were talking about this in terms of the relationship of the kind of evolutionary arc by which these might develop in relationship to one another, that we may want to sort of ask the question of how infected this come about and where was this kinds of moments of switches? There's another point that we may want to consider in terms of the ancients. And of course, I think what we mean by the ancients here is (27/42)

maybe not entirely clear. I think it was the oral societies, preliterate societies, I think is what... Yeah, I'm not sure this argument is necessarily borne by the record. One way to think about this is there's this caves, the Neolithic caves, or one is being at Lascaux. One is at Chauvet in France and others at Lascaux. The one at Chauvet is about 32,000 years old. The one at Lascaux, which we had studied much longer, was about 16,000 years old. And so the distance, the historical record between the present Lascaux and Chauvet are all about 16,000 years. The Wehrner Herzog film that you might be familiar with is at Chauvet at the beginning. And one of things you see in the art that happens there is that there's a representation of animals and a representation of the world around these ancestors of ours. Everything is represented sort of in a kind of horizontal movement. But at Lascaux, 16,000 years later, there's this huge shift where things meet your gaze. The animal looks at you in (28/42)

the eye. There are pictures of people that will return to look at you in the eye. And so whoever made those was able to imagine that in the future, not in the present, there would be someone else who's looking at this picture who will have a gaze that will be observing this picture in the future and that can make this picture. Now, I can meet that future gaze through this image. There's a lot going on there. And so some have suggested that this kind of some kind of light bulb went on during this particularly recent period that allowed for this kind of anticipation of a kind of futural consciousness as being something to which and from which a kind of communication is possible. This is more what I would refer to more generally as the capacity for sapiens rather than as necessarily consciousness. But I think it nevertheless gets to the heart of the phenomenon that we're trying to hone in on here. So is the phenomenon, because I think you kind of mentioned it before we got to this point, (29/42)

which is that individuation, though it was something that was that evolved as a sort of an adaptive way of interfacing with the world, has at this stage become a kind of malignancy. No, no, no, no, no. Let me try to introduce a little bit of specificity into this as well. The individuation and the sense of individuation that I'm speaking of, the kind of would identify as a kind of particular, at this point, has become a kind of potentially rather malignant trait of some aspects of Western political culture is not the capacity for sapiens, is not the capacity for a kind of projective or futural or speculative intersubjectivity. That might identify with this in the cave scenario. That the scenario of the kind of projective intersubjectivity or projective interobjectivity is closer to what I was talking about the ethics of the object. However, what I'm speaking to in the book about the kind of crisis of individuation or kind of malignant forms of individuation, in many cases, a kind of (30/42)

suppression or forgetting of that basis of subjectivity in which a kind of fantastically fragile fiction of a self-sovereign, autonomous individual is understood as a kind of ontological principle, as the basis of how society works itself. That not just the relatively dubious sort of conventional liberal discussion that a society is made up of essentially of individuals that subsequently choose to enter into social contracts, but even further than that, that they don't really even enter into these social contracts, that they simply are these kinds of encapsulated atomized selfish automatons bouncing off one each other like billiard balls, acting in their intensive self-interest in ways that are clearly motivated by any number of cultural motivations. This is the individuation that I speak of in the book as being particularly troublesome. Right. A principle of emergence that through all of our competing self-interest, whether it's in the marketplace or in the political sphere, through (31/42)

that process emerges a kind of order, a hidden order, and that the world that we live in today results from the competing impulses and self-interests of these automata. What you're suggesting is, and you're not the only one, I mean, this is, I think I've talked about this a bit in the context of one episode where we explored the foundations of Protestantism and the Reformation. Right. Max Weber and so forth. Right, exactly. It's not a controversial view to take, but the reason I was bringing it up was because it does seem like one of the conclusions you draw is that if we want to transition to a more sustainable world and a world in which we can live, given, I think, the state of our technology, the capacities for both destruction and creation that these technologies allow, that we need to be able to get to a place where this hyper-individuation ceases to be, that we roll it back somehow. I think I've seen this, for example, what I consider to be hyper-individuation in terms of (32/42)

narcissism, like the outgrowth of narcissism in society. I don't know if that's what you mean, but I suppose try and clarify what I just said because I don't have obviously the same- Yeah, you know, I'm happy to, yeah, no, and I think there's consider an overlap in what we're suggesting here. The question of emergence and order is an important aspect of this, and I'm not suggesting that the principle of the internal dynamics of complex adaptive systems that are not directed, that there is not only a capacity for the emergence of bottom-up order, but that this is one of the fundamental principles of complex adaptive systems themselves, whether those are physical or social or cultural linguistic. I think this is indisputable. However, there are one of the other emergent properties of those systems, which I think goes back to this question of to sentience and sapiens. One of the emergent properties of those systems can also be the capacity for self-modeling, that the entire system itself (33/42)

becomes in a way capable of modeling itself and deliberately acting back upon itself, that there becomes a capacity for certain kind of deliberate and deliberative recursion within that system, that there is emergence and then this emergence also has a kind of, let's say, a kind of second or third order cybernetic capacity for a feedback and recursion. This is also a form of intelligence. This is also a form of collective sapiens, not just individual sapiens, but a kind of collective sapiens. It implies foresight. It implies regulation. It implies structuring. It implies composition. This itself is a reflex, a capacity of which we are very capable, but have to a certain extent lost some expertise in. When I speak of the kind of crisis of governance in the West, this is really what I mean. What I mean is that we have lost this ability really to perform these feats of recursive regulatory compositional structure. Again, it's not that emergence isn't real or emergence is important, but (34/42)

one of the things that also should emerge is this capacity for recursion. How much is it that the capacity for recursion is inadequate or diminished? How much of it is that the map of the territory is no longer accurate, that the simulation that we're running of the real of reality has increasingly become unmoored from reality itself, and that this is what we are experiencing and that this is what the pandemic brought to the fore. Yeah. No, we're on the same page here. I think it's both. And both meaning that both the model of the real that we are producing is inadequate to the purposes of this recursion. And also, after 40 years, 50 years of kind of deliberate dismantling and deconstruction of the principle of governmentality itself, the impetus or inclination to enter into this recursion itself is atrophy to a certain kind of degree. So a couple questions there. One, what do you attribute to that, to the unmooring, to the increasing disconnect between the simulation and reality, or (35/42)

the simulation as an appropriate model of what reality is so that we can act upon in an effective way? And two, is the attack on institutions or the deconstruction of the systems of self-governance, et cetera, do those result in part from, actually, I'll just pose it as a question. What does that result from? But take the first one first, if you don't mind. Yeah, let me take the first one because I think what you've hit upon here is an important point. It might be worth sort of walking it through a little bit. So we have a tremendous capacity for producing incredibly rich models and simulations of the past, present, and future. Our capacity to produce these models as forms of technical abstraction is not atrophied whatsoever. I think probably, if nothing else, earth science and climate science are exemplary of this, I will make the argument that the very idea of climate change itself, not the phenomenon, but the concept of it, is an epistemological accomplishment of planetary scale (36/42)

computation without this massive planetary scale sensing and modeling and computation capacity that takes billions and billions of data points and produces model simulations of earth, past, present, and future through them. Simple heuristics like a hockey stick don't occur. But to your point, like we see with our science, the problem now is not really that the models are not accurate enough. Like if we could just get this out to 17 decimal points instead of seven decimal points, then we would have a better bottle of it. We would know what to do. No, what's happened is that model of the world, of what the future, this collective model of what the likely future of our ecological substrate, upon which all of our economies from which they emerge is in danger, that model itself does not have the capacity to have an effective recursive effect back on the real. The climate model cannot recursively affect the climate in the same way. And that is the problem. We see that in many respects, (37/42)

financial model. Because the climate model is a model of a physical system. Well, it's a model of a physical system. And the institutional structures that we have constructed in relationship to this model are not ones that activate this model as an instrument of governance. It is merely a representation of a possibility. Many financial models, for example, it's a descriptive model as opposed to a prescriptive one. It's a descriptive model as opposed to a recursive one. Is it as opposed to a recursive one? So many financial models are recursive in ways that climate models are not, in that financial models can in fact cause the thing to happen that they are modeling. Donald McKenzie's book, An Engine, Not a Camera on the History of Sock Exchanges, kind of towards this. So that's the second part of your point, where there's a problem or crisis, if you like. There's this mismatch between we have this tremendous technological capacity to produce models of the world and this tiny little (38/42)

T-Rex arm capacity to actually use those models to recursively act back upon the world in a way that would make those models tools of governance. The first part though about are the models, we're making the wrong kind of models. This is also true and this, I think, does to go to a certain degree goes to the question of this question of individuation and the question of what I would consider a kind of historically catastrophic misuse of our computational capacity towards the tracking and modeling and simulation of individual user behavior, individual consumer behavior that has amplified not only this kind of model of society as being an aggregation of atomic atomized individuals, but has amplified and accelerated that atomization even further and has even structured its own critique. That even the critique of surveillance capitalism from Shoshana Zuboff or others is predicated on the idea that of course computation is about modeling individuals, but now what needs to happen instead of (39/42)

these coercive contractual relationships between individuals and predatory platforms, these individuals must counter-weaponize themselves and take back their individual private data. The problem, however, is this hyperindividuation of the use of computation itself as if the individual human were the proper unit of analysis for how it is that the computation would model the world. Unless this is in a sense, is sort of repurposed towards things that are more beneficial, I don't think any amount of kind of political solutionism that we might get from the surveillance capitalism critique is going to be very helpful. It also seems to speak to a larger sense of consciousness for a planet that can view itself and act upon itself in a way that is simply not possible at the individual level. I want to move the second part of our conversation into the overtime, Benjamin, and that's going to give us an opportunity to really talk about what a post-pandemic world would look like if we were to (40/42)

implement some of these solutions that you feel are needed and what it would look like if we didn't. In other words, what is the sort of path of least resistance if things continue to move as they are today and what this means in both cases for the nation-state. We've talked about it a bit for the individual, for corporations, and for I think peace security and quality of life. For anyone who is new to the program, Hidden Forces is listener-supported. We don't accept advertisers or commercial sponsors. The entire show is funded from top to bottom by listeners like you. If you want access to the second part of today's conversation with Benjamin, as well as the transcripts and rundowns to this episode and every other episode we've ever done, head over to hiddenforces.io and check out our episode library, or subscribe directly through our Patreon page at patreon.com slash hiddenforces. There's also a link in the summary page to this episode with instructions on how to connect the overtime (41/42)

feed to your phone so that you can listen to these extra discussions just like you listen to the regular podcast. Benjamin, stick around, we're going to move the rest of our conversation into the overtime. Every episode, check out our premium subscription available through the Hidden Forces website or through our Patreon page at patreon.com slash hiddenforces. Today's episode was produced by me and edited by Stylianos Nicolaou. For more episodes, you can check out our website at hiddenforces.io. Join the conversation at Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram at Hidden Forces Pod, or send me an email at dk at hiddenforces.io. As always, thanks for listening. We'll see you next week. (42/42)

What's up, everybody? My name is Dimitri Kofinas, and you're listening to Hidden Forces, a podcast that inspires investors, entrepreneurs, and everyday citizens to challenge consensus narratives and to learn how to think critically about the systems of power shaping our world. This episode was released early to premium subscribers last week, and it features someone who truly needs no introduction. And for those of you who may not know Muhammad Al-Aryan, he is the president of Queens College Cambridge and chief economic advisor at Aliyahns, the corporate parrot of PIMCO, where Muhammad was CEO and co-chief investment officer from 2007 to 2014. Muhammad is a remarkably gifted communicator who is intimately connected to the global policymaking community. This makes him uniquely valuable to speak to during a time when the prospect of a policy failure is arguably the single biggest risk factor facing markets and the global economy. I asked Muhammad to appear on the podcast today because I (1/43)

believe that we are entering a very dangerous period in financial markets. As investors, we've all been conditioned to believe that markets always go up, that dips are always meant to be bought, and that when things don't work out, central banks are here to bail us out. But in a world where inflation is persistent and policymakers around the world have begun raising rates and contracting credit, continuing to bet on mean reversion could prove to be a deadly strategy for investors. My objective in this conversation is to give you a framework that you can use to navigate a world that is transitioning from one of insufficient demand to insufficient supply, from historically low volatility to rising uncertainty, and from easy money to hard choices. This is true not only for central bankers, but also for investors like you and me. Subscribers to our Super Nerd Tier can access the transcript to this episode as well as the Intelligence Report, which is the cliff notes to the Hidden Forces (2/43)

podcast, formatted for easy reading of episode highlights with answers to key questions, quotes from reference material, and links to all relevant information, books, articles, etc. used by me to prepare for this conversation. Since this episode deals with markets and investing, I want to make it absolutely clear that nothing we say on this podcast can or should be viewed as financial advice. Financial opinions expressed by me and my guests are solely our own opinions and should not be relied upon as the basis for financial decisions. And with that, please enjoy this deeply enlightening conversation with my guest, Muhammad Al-Aryan. So Muhammad, it's great to have you on the podcast. You've been one of the more outspoken critics of the Fed in recent months. We've made the case for more hawkish forward guidance and also tighter monetary policy. What would you say are the risk factors that most concern you and that markets in the economy are grappling with right now, and how do those (3/43)

risks relate to the Federal Reserve's current stance on monetary policy and inflation? So my major concern is that we are witnessing a big policy mistake. We are in phase three of this policy mistake. And that policy mistake will unduly harm the economy, undermine livelihoods, and then also disrupt the market that could then have a negative spillback effect onto the economy. So if you think step back and think of what would happen to our economic recovery, it would be undermined not by private sector developments, not by the end of a cycle, but by the Fed being too late in taking its foot off the accelerator and instead having to hit the brakes very hard. So I'd love to go into that in more detail, specifically this idea of a policy mistake. What exactly do you think the Fed has gotten wrong here? So three stages of this policy mistake. Mistake number one goes back to 2020 when for understandable reasons they decided to adopt a new policy framework. The problem is that the policy (4/43)

framework they adopted was made for the world of yesterday, not the world of today. The world of yesterday was insufficient demand. The world of today is insufficient supply. The mistake number one is adopting a framework change at the wrong time that told the markets that they would be looking backwards, not forward in trying to contain inflation. Step number two, which was a much more obvious mistake, and many of us have warned against it, is that as early as March of last year, they decided to characterize the higher inflation as transitory, and they did not, quote, retire that characterization until the end of November when there was ample evidence, both from the companies and from the economic data, that inflation was not transitory. Mistake number three is what's happening today. By not moving early enough, they're going to be forced into a very hard pivot. They will bunch three sets of contractionary measures, and the risk is that this economy could not navigate through these (5/43)

three contractory measures. I'd like to explore that more, Mohamed, but you're so good at, I think, you're one of the best in the industry at really creating metaphors or mental frameworks that help people think about where we find ourselves on a big picture level. You did it in 2009 with the, quote, new normal hypothesis that we were moving into a regime of secular stagnation driven by structural impediments to growth. You did it again in how you describe central banks as the, quote, only game in town, which I think really captured the significance that central bank policy was going to play in informing the direction of markets and the, I think, decision-making framework for investors at the time. I'd love to take a step back here and understand what your framework is for where we are moving in today. You talked about insufficient supply versus insufficient demand, which was the issue during the stagnationary period. How would you describe where we find ourselves today, and what do (6/43)

you think are the key factors responsible for that? So I think if you were to look for the bumper sticker, we've entered in a world not just of insufficient supply, and that relates not just to the supply of goods and services, but also to the supply of labor, but also in a world in which we have either pressed polls or reverse on globalization. And that in itself has an additional set of consequences for the global economy. I think the first element insufficient supply, we live it every day. It's harder to get things. It takes longer to ship things around the world. It's become much more expensive. Oil has become much more expensive. Energy is more expensive. Gas is more expensive. And then there are labor shortages. I think all of us are exposed to these labor shortages. So we know what that world looks like, and there are certain aspects that are good about it, which is higher wages, and in particular, higher wages for the less well-paid, and that is good, but it is also (7/43)

inflationary more broadly. The second element we don't see as much, but it is consequential. For a long time, we were living in a disinflationary world. And the way I describe this is just think of what Amazon, Google, and Uber have allowed us to do. And I'm just using these as labels. It cuts out the middle person. So it provides us with lower cost. Google allows us to price search. We are less price takers, and we are more price setters. And then Uber, perhaps the least well-understood effect, but the most powerful, allows us to use existing assets to deal with supply problems. Those three things were very powerful, and they played it out for over a decade in causing disinflationary winds. Now we have a very strong counter force, which is the fragmentation of the global economy. If you're Australia and you've been doing business with China, you know what that feels like. Suddenly, the Chinese economy is no longer available to you, both on terms of selling things and important things. (8/43)

We are seeing more regionalization, the emergence of blocks as opposed to globalization, and we are seeing very weak multilateral institutions. A perfect example of that, of how we are exposed to this, is vaccine inequality. Delta originated in India. Omicron originated in South Africa. And in both cases, the global system had failed to provide sufficient vaccination. We thought we were fine because we were highly vaccinated, but it turns out we are vulnerable to the parts of the world that are not. So we have to learn to live with a world that is more fragmented and where spillover effects are more pronounced. Is that another way of saying that you think that we're moving from a more open world to a more closed world? From a world that assumed openness was almost a given to one in which we are much less open, yes. I don't want to say closed because I don't think any economy other than maybe North Korea can live in a closed global economy, but certainly less open. Right. And I mean, (9/43)

another way of thinking about this, obviously, is that geopolitical tensions have been rising. And I wonder why markets don't seem to have reacted to rising geopolitical tensions over the last several years, the way that one would have expected them to if you had pulled an investor 10 or 20 years ago. Why do you think that is? I think there's two elements. One longstanding and the other one is more recent. Longstanding is very difficult to price by modal distribution. Look at what's happening in Russia and Ukraine today. It's either going to end up open conflict or it's going to end up diplomatic resolution. It's very difficult to be confident about one outcome. So you end up in a model's middle. You'd price neither outcomes. You'd price some average of the two that is least likely to materialize. But there's something else recently. And let me take you to the investment committee, to a typical investment committee in a sophisticated investment management company. You present a case (10/43)

for buying a certain bond, stock, whatever. And we go through all the fundamentals. Is it financially resilient? Is it well managed? Does it have a good market in front of it? And you convince us all that the fundamentals are green light. You will be asked a very important question. Who's going to buy after us? The subsequent buyer does two things that are very important for an investment. One, they validate your investment. Think of you buying an apartment. The minute you close on that apartment, what you really want is 10 people bidding for the apartment next door because the value of your apartment is going to go up. So the subsequent buyer validates your own purchase. But the subsequent buyer does something else as well. They provide you liquidity if you have to change your mind. Now I come along and I tell you, your subsequent buyer is a central bank. It is the Federal Reserve. It has a massive balance sheet. It has seemingly an infinite willingness to use it. And one more thing, (11/43)

it is price insensitive. It is not a commercial participant. It will buy regardless and it will turn up every single month with massive purchases. If I tell you that and you believe it because you've seen it now month after month, you will buy ahead of this. And whenever you see a geopolitical shock causing some pullback in asset prices, you will know that there's a big buyer out there. And it doesn't matter that they're buying just government bonds and mortgages because it ripples through the whole system. So the second reason why markets have been immune from geopolitical risk, in fact from almost any shock is there was a confidence that the Federal Reserve was our best friend forever. And don't underestimate how powerful that phenomenon was. That's why you hear consistently, buy the dip, Tina, there is no alternative, and FOMO, out. Okay, this is great because I do want to ask you about this. And we'll probably pivot again later back into geopolitics because I do want to ask you how (12/43)

you think they move towards a more multipolar world that we are currently living through will impact the decisions of governments to, let's say for example, one good example is in Europe, consider trade-offs between security and the welfare state. But in terms of the Fed, this is really fascinating because one of the questions I wanted to ask you is how does someone like you factor in things like behavioral conditioning or risk tolerance that change structurally as a result of the types of dynamics that you've described here, the reinforcement of buy the dip, and also the fact that investors now for years have become conditioned to this not just because of the Federal Reserve, but because of the historical empirical data that has shown convincingly that investors are better off being in the market and not selling, just using opportunities to buy. How do you think about that going forward if one of the major sort of legs under that stool gets taken out? Some great behavior in the power (13/43)

of behavioral science in understanding outcomes. It doesn't explain everything, but it sets that extra bit of insight that's really important. We're coming from a period in which investors have been deeply conditioned to buy the dip, and they've had consistent confirmation that that is the right thing to do. There was a reason why that is happening is very visible. It's called the Federal Reserve injecting as much as 120 billion of liquidity each month into the marketplace. It has been reinforced by experience, and because of that, a couple of things happened. The dips became smaller in duration and in magnitude, and that was critical. And two, because of that, volatility came down. And when volatility comes down, there are models that encourage people to put more money at risk because the volatility of your investment is lower. So you've had this reinforcing behavioral and structural technical playing out, and the result of that were three incredible years of returns. To think that (14/43)

we've had 20% basically average returns for the last three years, while we've had COVID, geopolitical problems, all sorts of other issues is incredible. But it is explained by this mix of not only liquidity, but behavioral aspects. Now, behavioral aspects are really difficult to predict, but you've got to keep on looking every single day. In the marketplace, the biggest change in behavioral aspects was when the marketplace goes from thinking in relative terms to thinking in absolute terms. There's this famous story of someone who comes home with a dog and declares to his family proudly that he paid $40,000 for this dog. And the family looks and says, you did what? And the response, he says, yes, it was a great deal. The cat was selling for $50,000. That is what's called a relative mindset. You continue buying not because what you're buying has value in itself, but it has value relative to other assets. And that can go on for a very long time. So when the Federal Reserve takes down and (15/43)

makes it onerous to hold bonds, you are pushed into taking more and more risk. And that works great. At some point, you get the pivot from relative to absolute. At some point, someone says, is a dog worth $40,000? And there is a wake-up call for everybody. I grew up in emerging markets. I cannot tell you the amount of times I've seen this regime shift. And they are violent when they occur. So it is very difficult to predict when this regime shift will happen. The good news is when it does happen, if you understand it quickly enough, you have time to get back on site. So again, a lot of really great points. I want to try to pull them out and address the Metsha individually. The first has to do with investor expectations and how these expectations have been shaped by the reassuring posture of central banks who have stood ready to, quote, buy the dip and provide the liquidity necessary to both elongate the bull market and perhaps more consequently for the purposes of credit and leverage, (16/43)

reduce volatility. Do you think that this conditioning has made markets more resistant to embracing this new regime of insufficient supply, spotty liquidity, et cetera, that you think we're moving into? And if so, what does that mean for the type of volatility that we should be prepared to see once markets try and readjust? That's my first question. Maybe the more broader question here is why do you think the Fed, if you agree with this, the Fed and other central banks didn't accurately factor into their tightening cycle the risks to financial instability, that they were focused very much on employment and on inflation, but they were maybe not taking enough account of the more difficult things to measure like capital misallocation or unsustainable business practices? So let me suggest on your second question first, if I may, on your second question, that is the other way around, that it is because the Federal Reserve was so worried about financial instability that it ended up with a (17/43)

pedal to the metal approach when the economy would have called for something else. Let's take the fourth quarter of 2018. A relatively new Federal Reserve chair comes in, recognizes that the Fed had been co-opted by markets, recognizes as a ton of moral hazard that had built in, recognizes there was an unhealthy codependency between the Fed and the markets, and in the fourth quarter starts signaling that the Fed was going to tighten policies consistent with economic developments. If you remember, at that time the economy was doing extremely well, markets were just fine, liquidity was abundant. Markets have their second day per tantrum. The first one was in 2013, May, June, they had their second one. This one plays out in the equity market in a big way and come the beginning of January 2019, Chair Powell undertakes a massive U-turn that is not warranted by economic developments. It was in response to financial instability. Now, if you are charitable, you would say, well, of course it's (18/43)

related to economic fundamentals because at some point the financial instability would spill back onto the economy. If you are less charitable, you would say it is yet another time that the Federal Reserve has proved that the Fed put is alive, that the minute the market is uncomfortable, is volatile, the Fed will have no choice but to be pulled back in. That is if you like, people traced that all the way back to 18 years ago to this conditioning of the market that there was a Fed put. In fact, the last period of instability, a lot of the narrative was in term of where is the Fed put? Where is the Fed put? Is it minus 10% on the S&P? Is it minus 20% on the S&P? I would say to you the problem is that the Fed became so sensitive to financial markets that it put that ahead of other things. It's a little bit like you fall into the trap of providing candy to your child. You recognize that you've provided too much candy. You try to stop. Your child has a tantrum. You decide that the (19/43)

consequences of the tantrum are not something that you want to live with and you give more candy even though you know that that is not a good long-term solution. That is where the Fed got stuck in and it worked as long as there was no inflation. Now that there's inflation, the Fed cannot do that anymore. And that's what the market is recognizing. Look, I am one who have said, no matter what you think of fundamentals, you should continue riding the liquidity wave. I've said this over and over again the whole of last year. I remember Leon Kooperman, a very famous and respected hedge fund manager, saying on TV that he was really worried about the markets and then he was asked, how are you positioned? And his answer was, I'm a fully invested bear. Yes, I'm a bear, but I'm fully invested because it's liquidity right now that is governing outcomes, not valuations. So people will ride that. Let me give you one last example if I may. At the end of 2007, a CEO of a major US bank came to see me (20/43)

and I asked him, where are we in the market cycle? And he drew an upside down you. And I said, where are we? He said, very near the top. And I said, how are you positioned? And he said, maximum risk on. And I said, how can you be maximum risk on if you need a top? He said, Mohammed's very simple. Number one, everybody else is maximum risk on. Number two is I don't know where the top is exactly. And number three is I'm confident I can reposition myself once there is unambiguous evidence. I remember that phrase, unambiguous evidence that we've turned. His bank had to be saved by the US government. So there is an inclination to ride these liquidity waves right till the end because the cost of premature exit is perceived to be quite high, especially when you judge on short term performance. So again, lots of really interesting threads to pull on here. Just with respect to this observation about both the fundamental unpredictability of markets, the difficulty, in other words, of timing a (21/43)

top, and the herd behavior and conditioning of investors. The chase momentum late into a cycle. How would you say that investors are set up going into this top, wherever it might be? And maybe you think we've already hit it. So it's still that very few people are comfortable taking on the momentum trade. And that's why we have seen equities recover, even though inflation is 7%. That is why we have seen equities do well, even though the yield curve has been flattening, signaling an increased possibility of a policy mistake. And what the other thing people have discovered is that we lack inherent liquidity. You know, if I had said to you a few years ago that a widely owned name that is deemed to be highly liquid in the marketplace could be down 25% in a few hours. You could wipe 250 billion off a market valuation. You would have said that's really unlikely unless this company is defaulting. Well, that's what happened to Metta, to Facebook. I was talking to someone who told me that they (22/43)

had difficulty trading Microsoft. That when the paradigm changes at that moment, there was a risk absorption in the system. And that tells you two things. One is many people are on one side of that trade, a trade that has worked extremely well. And by the way, it has continued to work relatively well. The losses of January were notable when nothing compared to the gains of the last few years. It tells you that it's still a very crowded trade, but it also tells you that there's structural illiquidity in the system. And that makes sense because since the financial crisis of 2008, we have shrunk by regulation the intermediaries. And we have increased significantly the end users, the non-banks. The ratio of non-banks to banks has gone up enormously. Now, the non-banks can't trade among each other very easily at all. They have to go through the banks. So when they want to reposition in a major way, there simply isn't enough risk absorption to allow that to happen without massive moves in (23/43)

prices. You've seen that with Amazon, you've seen that with Facebook, Metta, but we've also seen it with Snap up 62%. And I think we have to get used to the fact that when the liquidity goes out, we are going to have a lot more volatility, not just single name, but because of ETFs also for indices as a whole. Okay, so that actually raises two questions. The first question is, if we assume that the Fed has lost control of the inflation narrative and that inflation is in fact going to be sticky, it's going to be persistent, does that almost guarantee that the Fed has to hike us into a recession? And given your observations about liquidity, what does that mean for asset prices? And two, what guarantees do we have that the Fed would even be able to do anything about inflation since many of the sources of inflation this time around are supply driven and in some ways out of the Fed's control? So Dovers will live through the 70s and I was just learning economics at university. Remember what (24/43)

an inflation dynamic looks like. Younger people haven't lived through it. And inflation dynamics starts with a major disruption somewhere. In the 70s, it was the oil price increase. Today, it was supply disruptions, labor shortage. It's very local, it's lumber prices you will hear. And then next thing you know, it starts to be very broadly driven. It starts to be more persistent. And the reason why is if you're not careful, what is a reversible and temporary shock changes behavior. And that's why a lot of us, actually a few of us as early as April last year was urging the Fed to be open-minded. Don't call it transitory because you don't know. Have some humility. And what we've seen happen is that the shock may well have started in a certain place, lumber, chips. Next thing you know, it starts disrupting supply chains. It spreads. That's phase one of an inflation process. Phase two is what's called adaptive expectations and we are seeing it today. As people realize, they've been hit in (25/43)

real terms and they want to compensate. Companies start passing on prices to their final consumer without any hesitation whatsoever. And then wage earners start requesting higher wages. That's exactly what has been playing out. Phase three is the most dangerous one. It is when the expectation formation is not just adaptive, you're not just trying to compensate for past inflation, but becomes anticipatory. You start wanting to compensate for future inflation. At its extreme, and I'm not saying we're going anywhere near that, we are not. We're not going back to the levels of the 70s, even though we are following the dynamics of the 70s. At its extreme, it becomes hyperinflation. Now, the Federal Reserve cannot deal with the first shock, but it can deal with what happens thereafter. This Fed had the wrong framework, part one of the mistake, got stuck in a transitory characterization of inflation, part two of the mistake, and part three, it failed to move when it could move. You can go (26/43)

back and though I and others were urging the Fed to slowly take his foot off the accelerator by reducing QE last summer, because what we wanted to avoid is what's going to happen now. The Fed is going to be forced into a bunching of three contractionary measures, and that threatens the economy in a way that was avoidable. It will end its asset purchases. They should have already done that a while ago. It will start raising interest rates and it will look to reduce its nine trillion, bloated balance sheet. And that is why we are now in the world of third or fourth best. The first best approach was to start early, go slowly, and make sure that the economy can accommodate. Now, the Fed is going to be forced into a major pivot, and we don't know what the consequences of that pivot is going to be. The marketplace is pushing it to increase interest rates at least five times in 2022. I would have never called for five interest rate hikes. I don't know whether our highly-leveled economy can (27/43)

absorb five rate hikes so quickly. Again, tons of great questions. One is, how does one think about the relative sensitivity of this economy today to interest rate hikes and monetary contractions? It's so easy to forget. The balance sheet is 10 times bigger than it was pre-2008. It's absolutely wild, 1,000%. But you mentioned the 1970s and that you're saying you don't think we'll see inflation like that, but we are seeing one similar to what we had in the 70s, which is rising energy prices. Can you not foresee the possibility that energy prices could get out of control similar to how they did in the 70s, especially given some of the explicit policy choices and ESG mandates that have been adopted by Western governments and corporations in recent years? So that's a really complicated question because lots of things have driven energy prices. But let me focus on a crucial point you just raised, is that the transition to a greener economy, to a more sustainable economy, is proving to be (28/43)

more complicated than we expected. And I think that this is showing us that it's not enough to agree on the destination. And I am absolutely committed to the destination of a more sustainable way of doing things. I'm absolutely committed to the war against climate change. But whenever you embark on a journey, it's not enough to say, I'm going towards a destination without spending time thinking about the journey. And it turns out that we didn't think enough about the journey, that we didn't realize you cannot substitute something with nothing. So we started the transition away from particularly polluting energy sources, and that is a good thing. But we didn't have the green energy available in enough magnitude. Because of that, gas and oil in particular, that are now being treated as transition energy sources, have seen their prices go up a long way. Now that causes two things. One is stagflationary forces, but that doesn't impact the destination. It just means the journey becomes less (29/43)

pleasant, but it also can erode political will. And already we've seen certain countries in the developing world re-open core minds to try and deal with this energy surge. And the more people do that, the more you lose political will, the more the destination becomes more elusive. So keep an eye on energy. It's really important. The first effect, the stagflationary force, will play itself out because people get priced out of energy-intensive activities. But the second effect is one that you really have to keep an eye on. All right, so let's switch back to geopolitics because that actually does relate to energy. It relates specifically to the cost-benefit analysis that leaders make in a multilateral framework, versus one where individual countries have concern for their national best interest and specifically their national defense. How do you think that changing expectations on the part of global leaders will manifest in terms of shifting alliances, bilateral agreements, and other (30/43)

forms of diplomacy and military buildup in Europe and Asia, and in particular in Europe where you've got these security trade-off that has happened ever since the dawn of the Cold War, where the Europeans have basically offloaded their security to the United States. And that has also given them the luxury to be able to come together in the form of the EU, which itself is sort of one question of the viability of that system. So for a long time, countries ran what I call a dual-option model. You had an option on the US for national security, and you had an option on something else, the EU, or more recently, China. So let's take the example of Australia. Australia is a member of the Five Eye Intelligence System. That is the US, Canada, UK, New Zealand, and Australia. That is the highest level of national security coordination. So Australia had an option on the US for national security. It also was pursuing links with China in order to pursue economic prosperity. That's the dual-option (31/43)

model, and it worked very well. In option pricing terms, the price of that option was very, very low. As US-China tensions build up, the price of that option becomes much more elevated. And at some point, as the factor happened in Australia, you are asked to make a choice. And believe me, the last thing these dual-option countries want to do is make this sort of choice. So the first thing is to recognize that this dual-option model worked fine when it was US and Europe. The US would stand by and let Europe pursue its ever closer union, because that was viewed actually as enhancing the national security of the continent. But it's very different when it comes to US-China with all the complications of that relationship. That is the first major change in the way the system operates. But there's another change that I think we should not underestimate. Coming out of World War II, we constructed a global system where the core, basically the US and Europe, were given massive privileges, and (32/43)

two in particular. The issuance of the reserve currency, which means that you give pieces of paper to the rest of the world and you receive goods and services, that's a great deal. And the second thing is that countries outsourced to the US and to Europe the management of their savings. So the US and Europe ran with a much higher level of savings than they would otherwise, which meant that their interest rates were lower than they would otherwise. Add to that, the US and Europe were given enormous power at the multilateral institution. Even today, the head of the World Bank is an American, the head of the IMF is a European. Even today, Europe and the US, with one or two other countries, can block major decisions at these organizations. Now that system works well if together with these privileges comes responsibility. And that is the implicit contract that the rest of the world had with this system. The core is privileged, but the core is responsible for the well functioning of the (33/43)

system. And to the extent that you have volatility, the Russian crisis, the Asian crisis, the Mexican crisis, the Argentine in default, they all happen in the periphery. 2008 was a great shock to that system, because the crisis happened originated in the US. 2017 was another shock to this system, because under President Trump, the US pivoted very suddenly to an America First model. And then today, there's a third shock to that system, which is that the Federal Reserve is in the midst of making a policy mistake. And that is the world's most powerful central bank. So the other thing that's happened to our global system that has made it less stable, more fragmented, that has made multilateralism much harder to pursue, is that the implicit contract itself is trusted by fewer people, or at least is not trusted as much as it was before. So what does that mean for the position of a dollar? And also, what does it mean for other, let's say currency like either foreign currencies of an emerging (34/43)