It's a no brainer for me to invest in SURGE right now. With Hive price going down, the discount on SURGE increases. The effective yield increases, it's almost 18% right now .

That 18% effective yield on SURGE does look tempting with Hive's price dip. Discounts like this can be a great entry point, though timing the bottom is always tricky. In my experience, focusing on long-term value over short-term swings pays off

Agreed, 15% is already a strong return in most markets. SURGE pushing past that with the current discount makes it hard to ignore for yield seekers. Long-term holding could really compound nicely here

Absolutely, DCA smooths out the volatility and takes the guesswork out of timing. It's a solid strategy for building positions over time, especially in markets like this

I usually just go by gut feel and check if the chatter online has died down a bit. Volume drops help too, but I'm no pro at reading the charts. How do you spot those moments?

Absolutely, small consistent investments compound over time. Starting early with whatever you can afford often beats waiting for a big sum. Market cycles show that time in the market usually trumps timing the market

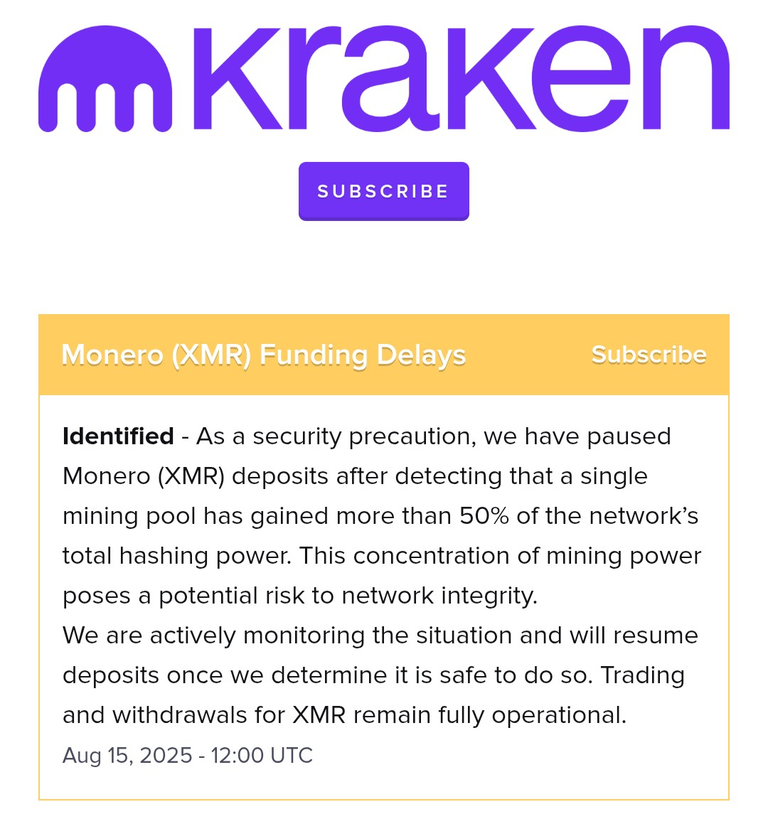

Exchanges don't need to worry about Dash transactions being reversed. Thanks to InstantSend and ChainLocks, all transactions are deterministically final, instantly.

The age of exchanges worrying about reorgs should be over. It can, if we want it to be.

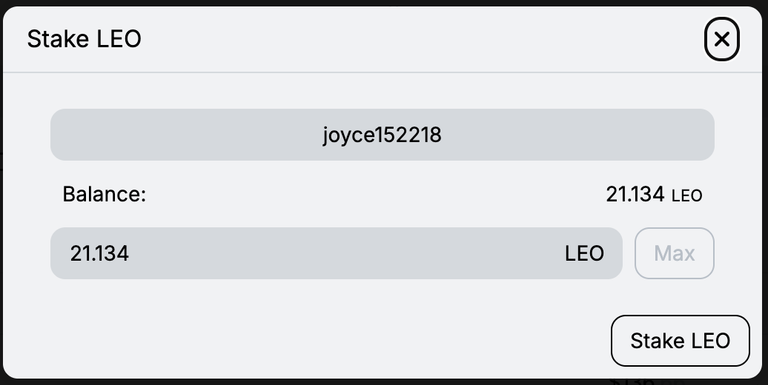

I firmly believe that LEO is going to hit $1 by the end of the year, and will probably go to $3-$5 next year. Both of those could happen sooner, but that's my thinking. With that in mind, I'm happy to keep scooping chips under 20 cents rather than paying 25, 30, even 50 cents. Still a 5x to $1 from here. Gets less and less the higher it goes. Simple math. I'm not selling below $1 so might as well get them as cheaply as possible.

Focus on your integrity and future work, not the drama. Build strong ties with supportive mentors, document your contributions, and let results speak louder than gossip. Protect your reputation by moving forward, not looking back.

Academic dismissal from your programme isn’t the end. After time away, you can often reapply or transfer credits. Focus on finishing strong, not past setbacks. Persistence counts.

And after 9-11 we did. And certainly after the reforms that Congress enacted. And the problem the Bush people had is that no matter what you do, the focus is going to be on them because they had the power. They're in office. And it can be uncomfortable. It can inhibit their capacity to plan and do additional things. And one of the maybe the most important contributions I made in 9-11 commission was to argue that we should not have minority reports, that we need to be unanimous. Because if we weren't unanimous, the public could- Was there a minority report? No. I was. But one of the few times in my life where I successfully argued for something and got it. So we didn't have minority reports. There were five Democrats and five Republicans. And they were selected in an extremely partisan environment. And thanks to Tom Cain and Lee Hamilton, it wasn't partisan. We didn't attack Bill Clinton. We didn't attack George Bush. Many of the criticism came from Republicans that thought we ought to (23/31)

2004 they said, oh my god, we better be a part of trying to beat back radical Islam or we're not going to survive. But I'm talking about 1991 where the United States came into the defense of Kuwait and station troops in Saudi Arabia. But the Saudis were concerned that Saddam Hussein would invade into Saudi Arabia. And they were grateful to have American troops in Saudi Arabia, weren't they? And they paid for it. Yeah, but what I'm saying is that they- Were they grateful? Yes. Yes, they were grateful and they didn't trust that bin Laden- and bin Laden wanted to do it himself. And he regarded it as an offense to Islam that we were on the holy soil where Mecca Medina are and that we invited a posthit. So what you're saying basically is that the Saudi regime is so unpopular and so corrupt that on the one hand they needed the United States to protect them against a state actor in Saddam Hussein with his army, but at the same time had to appease the radical Wahhabis. And so they were doing (26/31)

What's up everybody? I'm taking the next couple of weeks off and my release schedule for the end of August and the beginning of September is going to be a little irregular. I've already recorded another episode that I hope to release sometime in the next two weeks and I've got recordings lined up with all sorts of super interesting people including the former chairman of North America for Louis Vuitton, the co-founder of Kickstarter. John Meerschmeier is also coming on the show, which is great because I'm a huge fan of John's and it's always great to have a brainiac on foreign policy on the podcast. Who else? Michael Casey of Crypto Acclaim is coming on as is my good friend Mike Maloney who is long overdue for his hidden forces christening. It's going to be a baptism by fire. We're going to talk about gold, crypto, economic philosophy, and Tesla I'm sure because Mike and I have some friendly disagreements on Mr Musk. So that's going to be a lot of fun and there are a bunch of other (1/31)

great guests who I can't even recall off the top of my head but it's going to be awesome and it's a lot to look forward to. So what you're about to hear now is the overtime to my episode with Senator Bob Carey that was recorded in December of 2018 and it was the very first overtime segment that I released to our subscribers. I've chosen it for a number of reasons. First of all, I really liked it. I also really like Bob Carey. He's a really nice guy. It was a jovial conversation. He's a charming person. He's good-natured and I think that it is the type of conversation that's missing in politics today. I don't think every conversation should be like this but I think it would be nice if we had more of them where we could talk about politics in a way that was also just not necessary adversarial because I don't think that Bob Carey and I agree about everything. So it was fun. He's so funny and I think in that sense it'll be a joy to listen to but I also think it's informative. Bob Carey was (2/31)

one of the 10 9-11 commissioners and he actually gives his opinion about what he thinks the role of the Saudi government was in the 9-11 attacks which I think is a really big deal. It's something that Senator Bob Graham has spoken about. In fact, I asked him specifically about Bob Graham's work in this area. So in some sense the most remarkable thing about Bob Carey's admissions is how unremarkable they are. But of course if we had heard these statements back in 2001, 2002, the world may be a very different place today and certainly Saudi Arabia would have lost its single biggest ally and protector in the United States. So before I toss it to the episode guys, it is the end of August. I am going to take a little bit of time off. Don't expect anything next week. If there is something it'll be a surprise but we're going to pick back up in the beginning of September. I hope you all have a great end to your August and that you have some fun plans and in the meanwhile please enjoy My (3/31)

Overtime with Senator Bob Carey. All right, we're back. That was a nice break. That was a great break. So the one thing I want to ask you before we get to this at your experience in the commission, I asked you about Khashoggi and all this stuff now with the Saudis, we were talking about Elizabeth Warren 2020. What do you think is going to happen in 2020? Now we have now Donald Trump who's a phenomenon. I've never seen anything like him. Certainly Andrew Jackson could qualify maybe, right? But he was also at a different time. No, no, my God Andrew Jackson. Well they had to resuscitate him in the White House so he drank out his enigaration. He was pretty bad. Yeah, he drank big deal but he didn't lie every five minutes. But don't politicians all lie. It's just the way he... No, no, no, no, no. He's taking offense to that. Well, no, first of all, all of us lie. You find me a human being lying and he's the guy in the street corner saying the world's going to come to an end. So there isn't (4/31)

anybody that it's true that politicians probably lied 20% more than everybody else but we've never seen anything like Donald Trump. We've never seen anybody that covers his observations of what's going on in the world with things that are factually incorrect. So it's way beyond anything we've seen before. Well is it just about his lying or his facts or is it more about, to me, like... It's not just lying. It's taking credit for everything. There's a boastfulness that I find to be offensive because I don't think it's the way you get things done. I don't think you get things done by saying, I, I, I all the time. I agree. But for me now, it's not about the lying. What makes him so unique in that sense is the temperament. It's his temperament. Yeah, two reports that came out yesterday that were ordered by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, run by a Republican. It's a bipartisan group. He nanops vote to authorize those two reports. They provided these two organizations with all (5/31)

the stuff they had from Facebook, Google, all the other social media stuff that they had been provided, Twitter. Tell us what happened. That's what they said. First of all, they said what happened is these companies came before you and they didn't tell you the truth. But the most important thing is Vladimir Putin made a decision. He wanted Donald Trump to win the Republican primary. He wanted Donald Trump to win the general election and he contributed to that victory. And he's continuing through social media, through trolls, to try to deliver supporting messages that are consistent with what Trump is saying. Mueller's bad and Trump is good. It's fake news. It's big witch hunt and hoax. So I think overwhelmingly persuasive argument that he won because of Vladimir Putin. That doesn't mean he colluded with him. That doesn't mean he violated the law. But what it means is a foreign power decided to have a major impact and use our own... You think you had that big of an impact? Absolutely. (6/31)

Really? Oh my God. All you have to do is suppress the voters of 70,000 people in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania and you've got 270 electoral votes. Okay. So let's say that's true. Let's say... Well, it is true. We've got two lengthy reports that draw absolute positive conclusion that it's true and that it continues. Well, what I'm saying is we don't know whether ultimately it swung the election or not. But what I'm saying is... We do know that it swung the election. We know that... Absolutely know it swung the election. Okay. Hi, look, I don't know enough. Why are you laughing? You yielded so quickly. You're so funny. You didn't want to. You didn't want to. I figured this out. Look, I don't know enough to argue with you on that. It's funny that I told you this is what I saw when I watched you with Mira Carusa, Cabrera and CNBC. This is why I could tell that there are a lot of things, probably debates, that you... You probably enjoyed debates. Did you enjoy debating in politics? (7/31)

Were you just enjoying debating people like me who didn't know what they were talking about? No, no. I like a good argument. You do. Okay. So where I was going with that was... I'm going to use the word shit again. Was it because Hillary Clinton was such a shitty candidate for the Democratic Party and so many people didn't like her. She ran against Barack Obama in 2008, lost. If she had gotten 270 electoral votes, she'd be a genius. And were it not for Comey's two press conferences and the Russians, she would have got 270 electoral votes. Did she make a mistake? She didn't wow anybody though. Couldn't the Democrats have found a better candidate? I don't know. I mean... You don't have to say. A lot of people didn't like the Clintons and she lost in 2008 to Barack Obama and she still got the nomination and she railed out Bernie Sanders. She didn't rail Bernie Sanders? My God. Look at the facts and answer this question. Who has done more for the Democratic Party? Hillary Clinton or Bernie (8/31)

Sanders declares he's not even a Democrat. He wasn't independent up until now. Hillary and Bill Clinton have been out helping Democrats for the last 40 years. It's not surprising that people who they helped are saying, yes, we'll help you win. That means that the Democratic Party was representing itself, its own interest, and not the interests of the American people. No. First of all, it means that there's a human side to politics. I'm not doing something bad if I help somebody who helped me. We typically think that's a good thing for somebody to help somebody else who's been helpful to them. That's what Hillary was. She was a very good thing. But I think it's a little different when it comes to politics for the American people. Political parties are hard. Among the reasons I've burned it, probably pretty smart not joining the Democratic Party because you don't have to go to the conventions. You don't have to argue the policies. You don't have to put together a platform. You don't have (9/31)

to walk out with people mad at me because you supported a woman's right to choose and you had an argument with somebody who don't and you won and they didn't or vice versa. These arguments, you can end a friendship as a consequence of working in either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. They're hard work. That's an interesting point you brought up. It's a rough thing. I've actually definitely lost two friendships as a result of this recent electoral cycle. I find myself, and the reason why is because I've become really aversive to ideological extremism. I often find myself getting in trouble with people who I'm friendly with or friends with or even the audience on the right. I've had people in the audience criticize me for sounding bias, being biased against the right wing and also the same thing, bias towards the left wing. I feel like people are so ideological and not willing to meet somewhere down the middle. To see the other side as a human being. I completely agree with (10/31)

that. It's hard. By the way, you asked me earlier, I like getting arguments. There are times I get in ferocious arguments that people get up and walk out of the dinner. It happens. Then you got to apologize and move on. When was the last time that happened to you? Last night. That actually happened to me a few months ago. It doesn't happen to me often. I didn't walk out. I didn't mind it. My sister, who was in the legislature for a while in Nebraska, and she's at least as good as I am, but people that know both of us, she thinks she's better. We once went to a restaurant, we're having dinner with our families and it's crowded and it was like, you know what a Petri dish is? In a Petri dish, you can see the bacteria is spreading. In our case, we're sitting there and also we look around and everybody had been close to us and left because we're screaming at each other. That's how my family is. That's very funny that you guys are like that. I'm also a Greek family. We yell. Let me ask you (11/31)

one more question before we get to the 9-11 commission. Do you have any guesses about what's going to happen in 2020? Who the Democrats are going to run? What's going to happen with Trump? Is he going to be impeached? What's going to come out of the Russian investigation? Any predictions? Well, I don't know if I could keep it short enough to be done by midnight. The 20 election, I think the odds favor whoever is the Democratic nominee winning the general election. There are way too many people who are Republicans who are saying, I'll vote for anybody other than Donald Trump. Do you think the Democrats have it in the bag? No, I don't think anything is in the bag. That's the thing with politics. If you get it in the bag, then you don't. It's a shit show. No, you just don't know. I mean, I think the likelihood of President Trump winning Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, and he's got to win all three of those. The election comes down to that. If you win all three of those, you're (12/31)

going to have two and a seven electoral votes. Either candidate. I think it's much more likely this time around that all three of those states wear, by the way, we now have three Democratic governors. So I think it's much more likely that happens, and it certainly is going to be true that who of the Democratic nominee is, they know that that's the case. They know they cannot afford to lose those three states. Oh my God. Do you think he'll be impeached? Do you think there's any chance of that? What do you think will come out of this investigation, and why has it taken so long? Relative to every other special prosecutor. It's a fast-moving operation. How long did the Nixon Watergate stuff take? Like two years ago? Almost three years. Yeah. I mean, Clinton's went on from just after he came into, I mean, like seven years or something like that. So they take a while. Mueller's actually moving relatively fast. He's an extraordinary guy. I mean, Washington is a town where everything leaks, (13/31)

and he hasn't leaked anything. No one's been here. Trump's scared? Oh my God. He's terrified. He's going to send Cohen to jail. Yeah, he's going to jail. He's got three years. Right. For lying. Not for lying, but for violent. And Trump is a part of that transaction. It's not persuasive. Just say, well, he's my lawyer. He's going to do it. No, you tell your lawyer what to do, especially Trump. That's his whole modus operandi. Sue him. He tells the lawyer. But that's the thing that's so crazy about Trump. No. What I mean is the fact that he'd be on Air Force One, and he would tell people, no, I didn't know about it. And the next day, yeah, I did know about it. That's crazy. You can sue another human being and intimidate him. You can't sue the Department of Justice and intimidate him. So the big question is, if he doesn't win in 2020, will the Southern District bring a charge against him? And I think it's way better than 50-50 that they will. Yeah. Well, that's for sure. I think it's way (14/31)

better than 50-50 if they go into a court of law, he's going to have to have a pretty serious plea bargain to avoid jail time. He's in trouble if he's not president, that's for sure. It is challenging to impeach him if he's president. These two reports that came out of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, those two reports are devastating. And because they provide a background that if, and I don't know what Mueller's going to have, I mean, whether Mueller, he actually is finishing his work as he goes. This is in a situation where he gets all the way done, like Ken Starr, here's the report, and you got to do something with it. But he's got 17 people, he's already indicted or sent to jail, and he's seriously going through this thing. That's scary. And the next one is probably Donald Jr. And then he's going to take the question as the president himself. Do you think Donald Jr. is going to jail? I don't know. I don't know. But I... You don't have the answers? I don't. I don't. I (15/31)

mean, that's a really good thing about Mueller's done is he's kept it very, very confidential. I actually don't know. But I do know is he's been very successful. So sticking on conundrums, on Trump conundrums, let's use the case of Khashoggi and Muhammad bin Salman. By the way, is it just me or are we obsessed with using acronyms for everything today? Now, everyone calls Muhammad bin Salman MBS. And this is like a thing. Have you noticed this? Everyone refers to people by acronyms. They used to call people by their real names. Now, they call them by their initials. It's easier. It's more... Sure, it's easier, but you know... It's certainly a lot easier with an Arab name. So... Yeah, for sure. Anyway, so Trump has... And by the way, that's what he likes. He prefers being called MBS. So it's not... Does he really? That's interesting. So this is a peculiar case, peculiar beginning with Trump and the fact that he has been so adamant about not holding MBS accountable. Why do you think that (16/31)

is? Well, I think I've got a lot of stake. Financially and... No, no, I mean... In Saudi Arabia. No, I wouldn't be surprised... Politically. I wouldn't be surprised if they come in as partners in a real estate deal after he's out of office. But no, I think Jared Kushner was given the responsibility for coming up with a plan from the Middle East. I think rationally thought, well, if I can get UAE and Saudi together with Israel, we ought to be able to come up with something... How big is an Israel in this, in other words? Like, an Idaho in Israel. I do think the Palestinian issue is a big deal. And I think if you can get something that is coming out of Saudi Arabia and UAE with Israel on board, I think it's going to be easier to sell. I mean, I think it kind of makes sense on that level. So they have a lot of stake there. And I think they have a lot of stake in the military. I mean, Trump is... You've got to give them credit for being honest on that. He said, I'm doing it for oil. I'm (17/31)

doing it for weapons contracts. So I think they've made a big bet on Saudi. And they're not the only ones. I mean, a lot of people getting money from the Vision Fund right now. That's 75% of that is Saudi money. And by the way, I think it is important that we help Saudi make this transition from, you know, basically an autocratic kingdom to something that has a more liberal foundation. I am not confident that MBS is the guy to get it done. And what Khashoggi has done, the Khashoggi case has done, has done, for me, a couple of things. It's shown how massively incompetent these guys are. I mean, 12 guys with a bone saw flying in and then flying back out. How hard was that to figure out? 100 and nothing vote in the Senate saying Khashoggi did it. But the president continued to say, well, we're not sure about it. But I think it's going to lead to a significant change in our policy towards the war in Yemen. I think that's going to be a good thing. But I'm not confident that MBS is going to (18/31)

pull this off. I mean, he announces women can drive cars. And what else does he do? He puts the women who are advocating for women drive cars in jail. So don't put me down on the camp of people that are optimistic about the transition to a more modern society and a more modern economy in Saudi Arabia. 15 years ago, we never would have heard any negative comments about Saudi Arabia. The criticism of Saudi Arabia began really with the Barack Obama administration. And I think a big part of that ultimately was about oil, right? And fracking and energy. 15 and 19 hijackers were Saudis. Right. So well, they were, you're right, they were. And you know a lot about that. And we put one of the 10, 9, 11, 11. Yeah, the first two planes that left the United States were carrying Saudis out of the United States. So exactly. The bin Laden family. Right. But that was totally swept under the rub by the media. That was not discussed. That wasn't something that we weren't told. I don't think I'm correct (19/31)

and say it was not totally swept under the rub. But you're right. It wasn't the major media story. Why wasn't it? Was it because the Bush family was so connected to the Saudis? No, I think it's genuinely a complicated story. I mean, one of the problems that the 9, 11 Commission had in addition to the running on a limited time frame, which limited our capacity to do all the things that you'd like to be able to do. And why was that? Because they just wanted to get it over with? Republican Congress would extend our timeline and the Republican administration didn't want to extend the timeline. Why? It was such an important investigation. It was an important investigation. And part of it is it's impossible for any but myself, including because I was there in the 1990s as well. I was there when the first attack, the 93 attack on the World Trade Center. Yeah, the 93 attack. Right. I mean, that was the same guys. And we were making fun of them. We called them nose here in Salami, you know, (20/31)

because they would try to get their deposit back on the right or truck. And we didn't size it correctly. We had supported the Mujahideen in Afghanistan all the way through the 1980s. The Russians leave in December of 1988. And what do we do? We basically say, well, that's done. And well, it wasn't done. Right. And you said you were on the Intelligence Committee when we were in the Senate, right? So you were getting a lot of these reports. Getting a lot of the reports. And so you were not caught by surprise that Ben Laden was involved. No, I was not surprised at all. I mean, we were first the 93 attack. We didn't put him on the 93 attack, but we knew it was coming from a group of Islamic individuals who believe that we're a threat to their vision for the world. So they regarded us as an enemy. And they guarded us as apostates. And they regarded us as a good thing if they could kill Americans. So that's what they were doing with the World Trade Center. And then the big one was the 98 (21/31)

attacks on our embassy in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi. And the coal. Well, the coal was 2000. But the Nairobi attack was a really sophisticated operation. That wasn't just a couple of guys, you know, lighting up a room with automatic weapons. I mean, that was a very sophisticated operation and a very successful operation. And we were 98 percent certain it was al-Qaeda that did it. And we were 100 percent certain that it was a coal. We just didn't respond. We let them keep their sanctuary in Afghanistan. We threw a couple of cruise missiles in there right after Bill Clinton said I did have sex with that woman after all. That was a wagged-a-dog accusation he's made against him. And we didn't do enough. We just didn't. We didn't warn the airports after we had information. The walls that were created between the FBI and the CIA were made it difficult. It is true the leadership was concerned about it. But we just didn't have a coordinated effort. And we certainly didn't have a global effort. (22/31)

attack Bill Clinton. And a lot of Democrats that thought we ought to attack President Bush. And that was among the reasons why it was difficult to extend the timeline. But the central problem was it was a conspiracy. It was a conspiracy going back. You've heard you say 30 years. Yeah. I mean, quite a long time. I mean- But when you say it was a conspiracy, you mean it was a conspiracy by the Mujahideen and by Al Qaeda. By factions. Yes. Yes. Yes. There wasn't a- What about factions of the Saudi government? At the highest levels of- That's quoting Bob Graham. He said that this goes up to the highest levels of the Saudi government. And he refers to the 28 pages that I referred to at the beginning of our interview that 60 Minutes has published a piece on. I think we're part of a joint congressional inquiry into the 9-11 attack that happened right after you guys released your- Yeah. Look at it. The world on looking at 9-11 oftentimes divides into different camps. And this camp, I can't (24/31)

imagine. I don't think it's credible that 15 Saudis could participate in an attack on the United States of America without somebody at the senior level knowing about it. So what does that mean? What does that mean in a word? They've got blood on their hands. But why would they do that? Why would senior members of the Saudi government want to be involved in an attack against the United States? Because the family made a decision. We're going to support the Wahhabis. We're going to support people who are- have really seriously radical beliefs about the world and that everybody ought to be like completely pure and follow our rules and we get to decide what the rules are. It's a radical form of Islam. But the family owed their existence to the Bush family. Their existence to HW Bush. No. They owed their survival. To the- That's what I mean. No. They owed their survival to the support of the Wahhabis. And it wasn't until they got to attack until Al Qaeda starts going after them in 2003 or (25/31)

this balancing act. Right. And that their involvement in 9-11 was a result of their need to appease these terrorists that were- That's correct. That's correct. Threatening their own regime. That's correct. Now, I need to be clear about something that I wasn't clear about. The 9-11 commission did not conclude that the Saudis were responsible for 9-11. On the other hand, it did not conclude, as the Saudis have been saying in court, that we vindicated them. We did not vindicate them. We did not say they didn't do it and we didn't say that they did. So what I expressed earlier was my own opinion based upon my own reading of the- both of the documents that we had as well as some of the documents that we didn't have. What I find confusing in this is how this would sit with George W. Bush and the Bush administration, knowing this as I'm sure they did, how that sat with them and why they would ship the family members out. Was that- Do you think something just had a blind loyalty? I don't (27/31)

really have any answer to the question. I don't- I don't know. All I know is that they were allowed to leave and I think part of it was they were afraid for their lives. They wanted to get out of here because they knew- Well, they were. The families were, but why would the Bush administration allow them out? You can take a benign point of view. My benign point of view would be I'd give them the benefit of the doubt and say, look, they knew with 15 Saudi hijackers on there that Americans might be saying, we want to punish anybody who's still here because I don't have any evidence that there was any other motivation behind that. Okay. So then why then did the Bush administration not call out the Saudis? Given what we're talking about here, I mean if Bush- I mean he was on the rubble in 9-11. He bombed Afghanistan, invaded Iraq. Why wouldn't he have put the Saudis on notice? What do you think? I mean, you've been in politics- Well, I think the Saudis were put on notice. I mean, they (28/31)

certainly knew that they- They fucked up. Well, yeah, when 15-year-old people were on those planes, they could hardly say that the Saudis weren't involved. So they were put on notice, but they didn't really, I would say, get religion until all of a sudden radical Islamic groups started to attack them. But they knew it. I mean, they had to know what the Wahhabis were doing. The Wahhabis were moving all over the world, the worst and relatively close area for them to go. They were in Mumbai, setting up schools and- Right. I do understand why the Kings did that, why the royal family did it, but I think it created major problems both for them and for us. Well, I think it raises questions that will never be answered for the American public because the Bush administration was Machiavellian in the extreme. We're living now in a time where the- What's his name? Is playing- Christian Bales playing Dick Cheney. Looks pretty good. Looks pretty good. It reminds me, I forgot how scary Dick Cheney (29/31)

was. Look, here's the thing. When you start off with the presumption that it's a conspiracy. Of course. Alternatives conspiracies are relatively easy to put in the storyline. It just is. I mean, I still get people to come up and say those Jews did it. The government did it. It was an inside job. Couldn't possibly have knocked those planes down. They were holograms. Yeah, they couldn't possibly have knocked those buildings down to the plane. I mean, there are alternative storylines that go on about 9-11, but I don't have any doubt about who organized it. I don't have any doubt it began with Ben Laden's desire to attack the United States. It was a series of events that led up to the attack on us on our own ground. I don't have any doubt about that at all. I know what Kaili Sheikh Mohammed's role was in this thing. I know- 93. Yeah, but not only 93, but again in 2001. It doesn't have anyone. Right. So I don't have any doubt about that. That's where it came from, but there's a lot of (30/31)

moving parts beyond that that you're right. We probably never will know. Yeah. Senator Kerry, thank you for spending so much time with me between two bathroom breaks. Yeah. Thank you for putting the bathroom so close. I had a great time having you on the program. Thank you. You're welcome. Nice to be with you. (31/31)

differently, reach a different conclusion than the consensus, feel that the price should be much higher or much lower, take action on that. This is the way to be a serious outperformer. You have to see things a little differently. You have to see what you believe is the error in the consensus. So you have to see things differently. But there's another requirement. You have to be right. And most of the time, the consensus does a pretty good job of being right, and you can't habitually have a non-consensus view and expect it to be consistently right. So the requirements are, you have to think differently and better. It's not easy. And this is a lot of what Charlie Munger meant when he said that investing is not easy. And yet this is the requirement. How else can you be a superior performer unless you see things different from the crowd and better? Do you come to your investment insights or your contrarian views gradually? Or have there been instances in your life where you have this (16/32)

What's up, everybody? Merry Christmas. Happy holidays. This show is coming out on Christmas Eve for our American listeners and Christmas Day for everybody else. As the title of this episode suggests, there will be a segment from my interview with Howard Marks. It's between 20 and 30 minutes. Let's leave it at that. So that'll come at the end of this, but I have an important announcement to tell you all about beforehand, which is that finally, after a year of promising you, my listeners, a Hidden Forces subscription, I've finally done it. It's a long story as to why it took so long, and I'm not going to get into it. But one of the benefits that it took so long is that now anyone who subscribes gets immediate access to the transcripts of every episode we've ever done and to over 50 rundowns, starting with episode 19, which are these beautiful show outlines with reference materials, charts, pictures, quotes, all the rest of it. So anyone who's a regular listener has heard me reference (1/32)

these documents. They're the outlines that I put on Twitter and my personal feed and pictures and photo shots. It's like the nerd porn that I put out on social media. It's great. It's what I create before every single episode. So going forward, I'm going to be incorporating subscriber feedback and input into how I construct these, and I'm going to make a bigger effort to include links and documents and things like that related to the show. So that's all going to be made available through our website. And my intention in making these materials available is so that they can serve as educational compendiums to the subjects that we cover every week. And the same goes with the transcripts, which I'm happy to improve upon with user feedback. Again, if people want links or notes incorporated into them, I went through a couple of companies in order to find the right ones for these. So if you find errors in the archive, email me so that I can get them fixed. But this is going to be an (2/32)

evolutionary process with the goal of always being able to help you get more out of every single episode. But again, like I said, the archive of the transcripts is going to go all the way back to the very first episode. So when you get the subscription, you have access to everything. But wait, wait for it. There's more. And the more is that the baseline subscription is actually an entirely new podcast feed that you can add to your podcast application and get overtime segments, afterthoughts by me about the show, special one-off episodes that I put together for subscribers. So basically, I've already done two of these that I'm going to release with my episode on modern portfolio theory and the evolution of financial theory with Daniel Parris, as well as my episode with Bob Kerry, Senator Bob Kerry, the former 9-11 commissioner, Medal of Honor recipient, former governor and senator from Nebraska, which I actually completed right before I'm recording this. In both of those cases, a huge (3/32)

chunk of that interview, even longer than the 20 to 30 minutes that I'm releasing with Howard Marks today, which was originally meant for the purpose of being an overtime segment for the subscription, are going to be made available for subscribers. So that's what's going to come with the subscription feed. And I'm going to be releasing at least one of these every other week, but I may just end up doing it weekly or maybe even more often. It depends on what feedback I get from all of you. Most importantly though, I don't want any of you to think of these things, the rundowns, the transcripts, the audio or any future additional notes or educational materials that I put together around the podcast. I don't want you to think of these things in transactional terms. This is not a transaction. I've been doing this show for almost two years and I haven't asked for anything or taken any sponsors. I've done this and I continue to do it because I love doing it, but that doesn't mean that I can do (4/32)

it indefinitely without finding a way to cover the costs of production and I don't want to rely on advertising. I don't want to be interrupting these conversations with product or service announcements or pitches or anything like that. And I think that this is totally doable because I'm not looking to use this as a way of generating income for myself. I just want to make sure that I'm not covering the costs of this show out of my own pocket so that it's sustainable as a long-term project, which is what I want it to be. So when I say this isn't transactional, what I mean is that almost all of the value of what I do is the show itself, which is free, has been free, and always will be free. The vast majority of people on earth will continue to listen to it without ever making the choice to contribute a cent to making it possible, which is totally fine. But a small percentage of you are going to make the choice to support the show. And it's you that all of us, most of all me, are going to (5/32)

be immensely grateful for. So let me cap this off with some specific actionable information about how this is going to work. I looked at e-commerce platforms and subscription services that I could deploy myself through my site and decided that the best way to do this was actually to integrate Patreon into the Hidden Forces website, which I've never seen done before. So we're going to be using Patreon, which makes this way easier for those of you who already have Patreon accounts, but you're going to be able to access all of this material directly through the Hidden Forces website. So right now, as I'm talking, if you can go to hiddenforces.io, when you open up any individual episode, you'll still see the tabs that you saw before, info, related, bio. And to the right of those, you're going to see tabs for transcript, notes, overtime, or whatever else. And if you go into those, you're going to see that you can sign up and subscribe to them by going through Patreon. And that stuff's (6/32)

eventually going to be made available through the site. So if you subscribe, Patreon will know that you're logged in and it'll be able to make that stuff available to you. And each of those is part of a different bundle. So for $10 per month, you can access the overtime, which is all the stuff I was just telling you about, the extra bit with Bob Kerry, where we talk about 9-11, the 9-11 commission, and I get his opinion on what the role of the Saudi government was, the highest levels of government, and what the Bush administration knew or didn't know. And then with Daniel Parris, same thing, we go into a lot of really awesome stuff that deals specifically with investment options around the conversation that we have. So in both cases, this is really high quality material that you cannot get on the normal shelf. So that's for $10 a month. For an additional $5 a month, you can have access to all of the transcripts. And then for an additional $10, you can get access to everything, (7/32)

including the rundowns. So I thought a lot about this pricing. It's not fixed in stone, but I feel very comfortable with it. And let me tell you why. I looked at what all the other shows were doing, and besides making extra audio feeds available, and in those cases, a lot of times, the audio will come out once a month, I haven't seen much in the way of what we're providing. This is a huge archive of material, and there's no commitment. You can cancel the subscription at any time. You can also support separate from the subscription. If you want to just give a dollar a month, you can do that. And you know what? I'll love you for it. That will mean a lot to me and to everyone else, that you took the time to support the show and what we're doing. Of course, you can also provide more, and then I'd really love you. So here's my promise to you. If we get to a place where all the costs of producing the show, including the rental of my studio, the payments to my editor, web hosting, and all the (8/32)

other costs associated with putting this thing together, if we get to a place where all of these costs are covered, I will make an announcement and we'll figure out how we can use any additional income to create new and better content and grow the show. Like I said, I'm not interested in using hidden forces to generate income for myself. The most important thing that money can buy from you right now is time. And that means time to focus only on creating new content and generating ideas for new shows or newsletters or whatever else. Okay. So before we get to Howard Marks, I also want to say that for anyone who travels on British Airways, you can now expect to find hidden forces listed on BA's in-flight entertainment. We just finished onboarding our episodes with them, so that makes two airlines, the other one being United, that feature our show, which is super exciting. Okay. So Howard Marks, this segment lasts for about 25 minutes or so, I think. It rivals the episode itself for (9/32)

quality of content, in my view. In fact, I think it might very well be better. I asked Howard Marks about the role of intuition, how he relies on it in the management of his portfolio, contrarianism in investing. This moved from active to passive, the transformation in American capitalism after World War II with professional managers and professional management at companies. And if this trend has kind of run its course. I also asked him for what he would do if he was getting out of college today and how he continues to motivate himself every morning to go to work at Oak Tree for free, as it turns out. But finally, before I throw it to Howard Marks, I want to say in all likelihood, I'm going to release an episode for New Year's. I'm going to be in Greece when this episode comes out, visiting my family, but I'm going to find a studio there, hopefully to be able to record an intro to that episode. Look for that on New Year's Day, but if you don't get it, it will just skip straight to the (10/32)

second week of January, since this is the holidays and it's tough to publish through that. So, Merry Christmas, happy holidays. Hopefully, I won't have to give you happy New Year until next week, but if I do, happy New Year and enjoy the Howard Marks overtime. Howard, thank you for staying for this overtime segment. This is the first time I'm actually doing it, so I'm looking forward to see how it goes. There are a few questions that I had in our regular rundown that I wanted to ask you, and then I've got a few special questions that I have just for this segment. One has to do with intuition, which is something that you write about in the book, and it came up a lot in our conversation where you sort of danced around it, but I didn't ask you about it directly, which is, what role does intuition play for you when you're managing your portfolio? I think a lot of it depends on your definition of the word intuition. I'm not talking about voodoo, I'm not talking about guessing, I'm not (11/32)

talking about throwing darts or deciding on the basis of which foot I put on the floor first in the morning, but I think that we have to make judgments, subjective, personal, qualitative judgments. One of my favorite quotes is from Einstein, who said, not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts. Not everything can be quantified, nothing about the future can be proved, so I think it all comes down to judgment. If you think about it, just about everybody has access to all the same numbers. Just about everybody has the intelligence to process those numbers equally well. The margin of superiority comes from people who understand better than others the import of those numbers, the inferences that should be drawn and the actions that should be taken. I think that these kinds of judgments are extremely important. Somebody I can't remember right now said, I'd rather be approximately right than precisely wrong. You can't attain that much precision in (12/32)

your life when you're making judgments about the future, but you talked before about the importance of experience. Observation, emotional control, insight, hopefully second level insight. These are the things that can permit you to do a superior job. Is that just also a necessity or a feature of how our brains work that we can only ... There are theories in neuroscience, specifically one I'm thinking about called cognitive load theory, which is why a lot of high performers wear the same stuff, Barack Obama, Steve Jobs, et cetera. So much power to make decisions and that allocating more of that to the unconscious is the way to maximize performance. Is that one way to think about it? The importance of it, that is. Yeah. I don't know if I would use the word the unconscious, but I guess I would say the non-quantitative. The most important questions about a given company are not what it's going to earn this year or next. The most important questions are what kind of business it's going to (13/32)

have in 10 years and what kind of success and what kind of market share. And so I think that those things, as I say, anybody can reach the quantitative conclusions. The qualitative subjective conclusions are what separates the winners from the losers. Another question I had for you that we danced around in the interview had to do with contrarianism. And you have this great quote in the book. I'm going to butcher it if I try to say it, wing it. But your point is that it's not just enough to be right. If you're right and you're part of the consensus and everyone else is right, then you're not going to make any money. You have to be right and you have to have a view that's different than the consensus, which is what contrarianism is. And you also make this great point about the difference between contrarianism and pessimism, which can often be conflated. Talk to us a little bit about this notion of contrarianism and the role it plays in superior investing. We've talked a couple of times (14/32)

about second level thinking. And it seems clear to me that if you think the same as others, you will reach the same conclusions. If you'll reach the same conclusions, you'll take the same actions. If you take the same actions, you'll have the same performance. And yet success in the investing business is performing better than others. So that process can't be the one that leads to success. You have to, at some point, diverge from the crowd. You have to develop a knowledge advantage. You have to see things differently. You know, one of the important phrases in investing is variant perception. You have to see things at some point differently from others. The way that everybody, the massive investors, sees a given company is what determines its stock price on a given day. It is a voting booth, as Ben Graham said, and everybody cast their vote on a given day for the value of Apple. And the consensus becomes the price. That's what a market is. And the big wins come when you see things (15/32)

revelation or this contrarian idea and you see something in that moment that you hadn't seen before and that no one else is seeing and it's a really great opportunity and you have to move on it? I mean, I wouldn't accuse myself of having many epiphanies. I try to be rather level in my views toward the markets. And then as the market changes, as the price of an asset changes relative to the asset's fundamentals, if the price rises relative to the fundamentals, I should gradually like it less until eventually if the price gets high enough relative to the fundamentals, I should absolutely dislike it. But that's a process of gradual accretion and not epiphany. The only time I think things change radically is when the world changes radically. September 14th of 08, most things were pretty much okay, people thought. September 15th, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and everybody thought that the financial world was going to end. So when the world changes radically, it makes sense that your (17/32)

view on the proper behaviors should change radically and we did. There's something else comes out of that question, which is that after 2008, we've seen this major shift away from active management towards passive. Right. A lot more people... In the stock market. In the stock market. More people have been moving to index funds, ETFs, et cetera. Is that a trend that you expect to continue? And the other question I have is if most investors are, as you say, on average, average, and in most cases, it may very well be a rational decision to put your money in an ETF or in an index fund as opposed to giving it to an average manager who will either do average or below average. And charge high fees. And charge high fees. The question is, well, where are the great managers and how does someone find one and then how do they give them their money? Well, this is the great dilemma and this is something that's really not easily answered. The trend toward passive investment really has... I mean, when (18/32)

I was at University of Chicago more than 50 years ago, this is when they first told me that on average, most people do average before fees and below average after fees. So you shouldn't pay somebody high fees to give you average performance. You should only pay people who are exceptional. We went through a period when pretty much everybody could charge fees commensurate with success when they weren't producing success. We have the Morningstar system, which gives mutual funds ratings, not on some absolute standard of whether they did a good job or whether they beat the stock market, but on whether they beat others. You can have a five-star rating and still have not done as well as a stock market, in theory. The point is that the first real index fund was formed around 1974. It gradually started to raise money. Nobody took it that seriously because somebody in the mutual fund industry that I won't name said, well, who's going to accept average performance? The answer turned out to be a (19/32)

lot of people will accept average performance if the alternative is below average performance. As the world has gotten smarter through the process that I described before, as people look at things more objectively, I mean that argument, who would settle for average? That's a great argument until you look deeply into what's really going on. When you do, a lot of people would say, I will. The average is pretty good. If I can get the average certainly and with low fees, I'm in. Now the trend towards passive has strengthened. Now something like 38% of all the mutual fund equity money is managed passively. Our next question is when will it stop? I think it makes sense to think that the trend will continue as long as the passives do better than the actives. We've been going through a long period here when the passives have been doing better than the actives. This year started off weak, which means that the actives who might have had less than full representation in the leading stocks (20/32)

outperformed, but then the market has turned strong in the last few months and now the active managers are behind again. I think that trend towards passive will not stop until passive underperforms for a while. I don't know when that'll be or what would make it happen, but it may happen at some point in time. The other question that's interesting, I wrote this last memo called Investing Without People, which started off with the discussion of passive investing. Passively as more and more money is managed passively and fewer and fewer people are out there looking for bargains, then we can assume I think that the level of so-called efficiency will decline and that it will become possible once again to get some bargains. That's my hope. That speaks to, in fact, you took the words out of my mouth, the move towards passive investing is not independent of this move towards market efficiency that we've been discussing during the interview and the financial markets and the size of the (21/32)

financial sector growing. Well, market efficiency makes it really hard to outperform. I think that in the last 40 years, people have concluded that markets are much more efficient than they used to think. There's another trend that we've seen over the decades and that has been this move since I think primarily after World War II of separating management from ownership. It's been a financial innovation that's really generated a lot of wealth and it's allowed the principles of specialization to work wonders in many cases. What we've also seen in more recent years is perversions of that. I think one perfect example is tying executive compensations to stock value and then stock buybacks and trying to game your income in that way. Do you feel that the benefits of that model have run their course or that there needs to be some sort of rejiggering of that? I think this is an important topic. I learned about this when I was in college, which was a long time ago. What I was taught was that one (22/32)

of the reasons that the free market system, capitalist system, the US economic system had produced good results was that whereas 100 years ago or maybe 150, companies were pretty much run by their owners. Eventually, we developed this thing called professional management. At an appropriate point in time, the professional managers took over from the founders and owners and brought skills that the founders and owners or certainly their children or their children's children didn't have. Managing companies was turned over from the owners and founders to professional managers who maybe had skills that the others didn't have and that this was a great source of our economic success. Makes sense. However, nothing's perfect. That's one of the bottom lines on life. Through this process, we developed basically two classes of people, the company owners and the company managers. It gets dangerous, as you say, when the managers are not responsive to the owners. If they paid themselves too well, if (23/32)

What's up, everybody? Merry Christmas. Happy holidays. This show is coming out on Christmas Eve for our American listeners and Christmas Day for everybody else. As the title of this episode suggests, there will be a segment from my interview with Howard Marks. It's between 20 and 30 minutes. Let's leave it at that. So that'll come at the end of this, but I have an important announcement to tell you all about beforehand, which is that finally, after a year of promising you, my listeners, a Hidden Forces subscription, I've finally done it. It's a long story as to why it took so long, and I'm not going to get into it. But one of the benefits that it took so long is that now anyone who subscribes gets immediate access to the transcripts of every episode we've ever done and to over 50 rundowns, starting with episode 19, which are these beautiful show outlines with reference materials, charts, pictures, quotes, all the rest of it. So anyone who's a regular listener has heard me reference (1/32)

these documents. They're the outlines that I put on Twitter and my personal feed and pictures and photo shots. It's like the nerd porn that I put out on social media. It's great. It's what I create before every single episode. So going forward, I'm going to be incorporating subscriber feedback and input into how I construct these, and I'm going to make a bigger effort to include links and documents and things like that related to the show. So that's all going to be made available through our website. And my intention in making these materials available is so that they can serve as educational compendiums to the subjects that we cover every week. And the same goes with the transcripts, which I'm happy to improve upon with user feedback. Again, if people want links or notes incorporated into them, I went through a couple of companies in order to find the right ones for these. So if you find errors in the archive, email me so that I can get them fixed. But this is going to be an (2/32)

evolutionary process with the goal of always being able to help you get more out of every single episode. But again, like I said, the archive of the transcripts is going to go all the way back to the very first episode. So when you get the subscription, you have access to everything. But wait, wait for it. There's more. And the more is that the baseline subscription is actually an entirely new podcast feed that you can add to your podcast application and get overtime segments, afterthoughts by me about the show, special one-off episodes that I put together for subscribers. So basically, I've already done two of these that I'm going to release with my episode on modern portfolio theory and the evolution of financial theory with Daniel Parris, as well as my episode with Bob Kerry, Senator Bob Kerry, the former 9-11 commissioner, Medal of Honor recipient, former governor and senator from Nebraska, which I actually completed right before I'm recording this. In both of those cases, a huge (3/32)

chunk of that interview, even longer than the 20 to 30 minutes that I'm releasing with Howard Marks today, which was originally meant for the purpose of being an overtime segment for the subscription, are going to be made available for subscribers. So that's what's going to come with the subscription feed. And I'm going to be releasing at least one of these every other week, but I may just end up doing it weekly or maybe even more often. It depends on what feedback I get from all of you. Most importantly though, I don't want any of you to think of these things, the rundowns, the transcripts, the audio or any future additional notes or educational materials that I put together around the podcast. I don't want you to think of these things in transactional terms. This is not a transaction. I've been doing this show for almost two years and I haven't asked for anything or taken any sponsors. I've done this and I continue to do it because I love doing it, but that doesn't mean that I can do (4/32)

it indefinitely without finding a way to cover the costs of production and I don't want to rely on advertising. I don't want to be interrupting these conversations with product or service announcements or pitches or anything like that. And I think that this is totally doable because I'm not looking to use this as a way of generating income for myself. I just want to make sure that I'm not covering the costs of this show out of my own pocket so that it's sustainable as a long-term project, which is what I want it to be. So when I say this isn't transactional, what I mean is that almost all of the value of what I do is the show itself, which is free, has been free, and always will be free. The vast majority of people on earth will continue to listen to it without ever making the choice to contribute a cent to making it possible, which is totally fine. But a small percentage of you are going to make the choice to support the show. And it's you that all of us, most of all me, are going to (5/32)

be immensely grateful for. So let me cap this off with some specific actionable information about how this is going to work. I looked at e-commerce platforms and subscription services that I could deploy myself through my site and decided that the best way to do this was actually to integrate Patreon into the Hidden Forces website, which I've never seen done before. So we're going to be using Patreon, which makes this way easier for those of you who already have Patreon accounts, but you're going to be able to access all of this material directly through the Hidden Forces website. So right now, as I'm talking, if you can go to hiddenforces.io, when you open up any individual episode, you'll still see the tabs that you saw before, info, related, bio. And to the right of those, you're going to see tabs for transcript, notes, overtime, or whatever else. And if you go into those, you're going to see that you can sign up and subscribe to them by going through Patreon. And that stuff's (6/32)

eventually going to be made available through the site. So if you subscribe, Patreon will know that you're logged in and it'll be able to make that stuff available to you. And each of those is part of a different bundle. So for $10 per month, you can access the overtime, which is all the stuff I was just telling you about, the extra bit with Bob Kerry, where we talk about 9-11, the 9-11 commission, and I get his opinion on what the role of the Saudi government was, the highest levels of government, and what the Bush administration knew or didn't know. And then with Daniel Parris, same thing, we go into a lot of really awesome stuff that deals specifically with investment options around the conversation that we have. So in both cases, this is really high quality material that you cannot get on the normal shelf. So that's for $10 a month. For an additional $5 a month, you can have access to all of the transcripts. And then for an additional $10, you can get access to everything, (7/32)

including the rundowns. So I thought a lot about this pricing. It's not fixed in stone, but I feel very comfortable with it. And let me tell you why. I looked at what all the other shows were doing, and besides making extra audio feeds available, and in those cases, a lot of times, the audio will come out once a month, I haven't seen much in the way of what we're providing. This is a huge archive of material, and there's no commitment. You can cancel the subscription at any time. You can also support separate from the subscription. If you want to just give a dollar a month, you can do that. And you know what? I'll love you for it. That will mean a lot to me and to everyone else, that you took the time to support the show and what we're doing. Of course, you can also provide more, and then I'd really love you. So here's my promise to you. If we get to a place where all the costs of producing the show, including the rental of my studio, the payments to my editor, web hosting, and all the (8/32)

other costs associated with putting this thing together, if we get to a place where all of these costs are covered, I will make an announcement and we'll figure out how we can use any additional income to create new and better content and grow the show. Like I said, I'm not interested in using hidden forces to generate income for myself. The most important thing that money can buy from you right now is time. And that means time to focus only on creating new content and generating ideas for new shows or newsletters or whatever else. Okay. So before we get to Howard Marks, I also want to say that for anyone who travels on British Airways, you can now expect to find hidden forces listed on BA's in-flight entertainment. We just finished onboarding our episodes with them, so that makes two airlines, the other one being United, that feature our show, which is super exciting. Okay. So Howard Marks, this segment lasts for about 25 minutes or so, I think. It rivals the episode itself for (9/32)

quality of content, in my view. In fact, I think it might very well be better. I asked Howard Marks about the role of intuition, how he relies on it in the management of his portfolio, contrarianism in investing. This moved from active to passive, the transformation in American capitalism after World War II with professional managers and professional management at companies. And if this trend has kind of run its course. I also asked him for what he would do if he was getting out of college today and how he continues to motivate himself every morning to go to work at Oak Tree for free, as it turns out. But finally, before I throw it to Howard Marks, I want to say in all likelihood, I'm going to release an episode for New Year's. I'm going to be in Greece when this episode comes out, visiting my family, but I'm going to find a studio there, hopefully to be able to record an intro to that episode. Look for that on New Year's Day, but if you don't get it, it will just skip straight to the (10/32)

second week of January, since this is the holidays and it's tough to publish through that. So, Merry Christmas, happy holidays. Hopefully, I won't have to give you happy New Year until next week, but if I do, happy New Year and enjoy the Howard Marks overtime. Howard, thank you for staying for this overtime segment. This is the first time I'm actually doing it, so I'm looking forward to see how it goes. There are a few questions that I had in our regular rundown that I wanted to ask you, and then I've got a few special questions that I have just for this segment. One has to do with intuition, which is something that you write about in the book, and it came up a lot in our conversation where you sort of danced around it, but I didn't ask you about it directly, which is, what role does intuition play for you when you're managing your portfolio? I think a lot of it depends on your definition of the word intuition. I'm not talking about voodoo, I'm not talking about guessing, I'm not (11/32)

talking about throwing darts or deciding on the basis of which foot I put on the floor first in the morning, but I think that we have to make judgments, subjective, personal, qualitative judgments. One of my favorite quotes is from Einstein, who said, not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts. Not everything can be quantified, nothing about the future can be proved, so I think it all comes down to judgment. If you think about it, just about everybody has access to all the same numbers. Just about everybody has the intelligence to process those numbers equally well. The margin of superiority comes from people who understand better than others the import of those numbers, the inferences that should be drawn and the actions that should be taken. I think that these kinds of judgments are extremely important. Somebody I can't remember right now said, I'd rather be approximately right than precisely wrong. You can't attain that much precision in (12/32)

your life when you're making judgments about the future, but you talked before about the importance of experience. Observation, emotional control, insight, hopefully second level insight. These are the things that can permit you to do a superior job. Is that just also a necessity or a feature of how our brains work that we can only ... There are theories in neuroscience, specifically one I'm thinking about called cognitive load theory, which is why a lot of high performers wear the same stuff, Barack Obama, Steve Jobs, et cetera. So much power to make decisions and that allocating more of that to the unconscious is the way to maximize performance. Is that one way to think about it? The importance of it, that is. Yeah. I don't know if I would use the word the unconscious, but I guess I would say the non-quantitative. The most important questions about a given company are not what it's going to earn this year or next. The most important questions are what kind of business it's going to (13/32)

have in 10 years and what kind of success and what kind of market share. And so I think that those things, as I say, anybody can reach the quantitative conclusions. The qualitative subjective conclusions are what separates the winners from the losers. Another question I had for you that we danced around in the interview had to do with contrarianism. And you have this great quote in the book. I'm going to butcher it if I try to say it, wing it. But your point is that it's not just enough to be right. If you're right and you're part of the consensus and everyone else is right, then you're not going to make any money. You have to be right and you have to have a view that's different than the consensus, which is what contrarianism is. And you also make this great point about the difference between contrarianism and pessimism, which can often be conflated. Talk to us a little bit about this notion of contrarianism and the role it plays in superior investing. We've talked a couple of times (14/32)

about second level thinking. And it seems clear to me that if you think the same as others, you will reach the same conclusions. If you'll reach the same conclusions, you'll take the same actions. If you take the same actions, you'll have the same performance. And yet success in the investing business is performing better than others. So that process can't be the one that leads to success. You have to, at some point, diverge from the crowd. You have to develop a knowledge advantage. You have to see things differently. You know, one of the important phrases in investing is variant perception. You have to see things at some point differently from others. The way that everybody, the massive investors, sees a given company is what determines its stock price on a given day. It is a voting booth, as Ben Graham said, and everybody cast their vote on a given day for the value of Apple. And the consensus becomes the price. That's what a market is. And the big wins come when you see things (15/32)

differently, reach a different conclusion than the consensus, feel that the price should be much higher or much lower, take action on that. This is the way to be a serious outperformer. You have to see things a little differently. You have to see what you believe is the error in the consensus. So you have to see things differently. But there's another requirement. You have to be right. And most of the time, the consensus does a pretty good job of being right, and you can't habitually have a non-consensus view and expect it to be consistently right. So the requirements are, you have to think differently and better. It's not easy. And this is a lot of what Charlie Munger meant when he said that investing is not easy. And yet this is the requirement. How else can you be a superior performer unless you see things different from the crowd and better? Do you come to your investment insights or your contrarian views gradually? Or have there been instances in your life where you have this (16/32)

revelation or this contrarian idea and you see something in that moment that you hadn't seen before and that no one else is seeing and it's a really great opportunity and you have to move on it? I mean, I wouldn't accuse myself of having many epiphanies. I try to be rather level in my views toward the markets. And then as the market changes, as the price of an asset changes relative to the asset's fundamentals, if the price rises relative to the fundamentals, I should gradually like it less until eventually if the price gets high enough relative to the fundamentals, I should absolutely dislike it. But that's a process of gradual accretion and not epiphany. The only time I think things change radically is when the world changes radically. September 14th of 08, most things were pretty much okay, people thought. September 15th, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and everybody thought that the financial world was going to end. So when the world changes radically, it makes sense that your (17/32)

view on the proper behaviors should change radically and we did. There's something else comes out of that question, which is that after 2008, we've seen this major shift away from active management towards passive. Right. A lot more people... In the stock market. In the stock market. More people have been moving to index funds, ETFs, et cetera. Is that a trend that you expect to continue? And the other question I have is if most investors are, as you say, on average, average, and in most cases, it may very well be a rational decision to put your money in an ETF or in an index fund as opposed to giving it to an average manager who will either do average or below average. And charge high fees. And charge high fees. The question is, well, where are the great managers and how does someone find one and then how do they give them their money? Well, this is the great dilemma and this is something that's really not easily answered. The trend toward passive investment really has... I mean, when (18/32)

I was at University of Chicago more than 50 years ago, this is when they first told me that on average, most people do average before fees and below average after fees. So you shouldn't pay somebody high fees to give you average performance. You should only pay people who are exceptional. We went through a period when pretty much everybody could charge fees commensurate with success when they weren't producing success. We have the Morningstar system, which gives mutual funds ratings, not on some absolute standard of whether they did a good job or whether they beat the stock market, but on whether they beat others. You can have a five-star rating and still have not done as well as a stock market, in theory. The point is that the first real index fund was formed around 1974. It gradually started to raise money. Nobody took it that seriously because somebody in the mutual fund industry that I won't name said, well, who's going to accept average performance? The answer turned out to be a (19/32)

lot of people will accept average performance if the alternative is below average performance. As the world has gotten smarter through the process that I described before, as people look at things more objectively, I mean that argument, who would settle for average? That's a great argument until you look deeply into what's really going on. When you do, a lot of people would say, I will. The average is pretty good. If I can get the average certainly and with low fees, I'm in. Now the trend towards passive has strengthened. Now something like 38% of all the mutual fund equity money is managed passively. Our next question is when will it stop? I think it makes sense to think that the trend will continue as long as the passives do better than the actives. We've been going through a long period here when the passives have been doing better than the actives. This year started off weak, which means that the actives who might have had less than full representation in the leading stocks (20/32)

outperformed, but then the market has turned strong in the last few months and now the active managers are behind again. I think that trend towards passive will not stop until passive underperforms for a while. I don't know when that'll be or what would make it happen, but it may happen at some point in time. The other question that's interesting, I wrote this last memo called Investing Without People, which started off with the discussion of passive investing. Passively as more and more money is managed passively and fewer and fewer people are out there looking for bargains, then we can assume I think that the level of so-called efficiency will decline and that it will become possible once again to get some bargains. That's my hope. That speaks to, in fact, you took the words out of my mouth, the move towards passive investing is not independent of this move towards market efficiency that we've been discussing during the interview and the financial markets and the size of the (21/32)

financial sector growing. Well, market efficiency makes it really hard to outperform. I think that in the last 40 years, people have concluded that markets are much more efficient than they used to think. There's another trend that we've seen over the decades and that has been this move since I think primarily after World War II of separating management from ownership. It's been a financial innovation that's really generated a lot of wealth and it's allowed the principles of specialization to work wonders in many cases. What we've also seen in more recent years is perversions of that. I think one perfect example is tying executive compensations to stock value and then stock buybacks and trying to game your income in that way. Do you feel that the benefits of that model have run their course or that there needs to be some sort of rejiggering of that? I think this is an important topic. I learned about this when I was in college, which was a long time ago. What I was taught was that one (22/32)

of the reasons that the free market system, capitalist system, the US economic system had produced good results was that whereas 100 years ago or maybe 150, companies were pretty much run by their owners. Eventually, we developed this thing called professional management. At an appropriate point in time, the professional managers took over from the founders and owners and brought skills that the founders and owners or certainly their children or their children's children didn't have. Managing companies was turned over from the owners and founders to professional managers who maybe had skills that the others didn't have and that this was a great source of our economic success. Makes sense. However, nothing's perfect. That's one of the bottom lines on life. Through this process, we developed basically two classes of people, the company owners and the company managers. It gets dangerous, as you say, when the managers are not responsive to the owners. If they paid themselves too well, if (23/32)